- Home

- Неизвестный

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Read online

“Good morning, Miss Rodgers!” said the young man, in the free manner usual with him toward pretty and inexperienced country girls.

Felicity Sims, the young lady, instantly perceived how the mistake had arisen. Miss Rodgers was the owner of a blue coat, exceptional for the small village, and Felicity, in a spirit of envy, had bought a similar article for herself, which she wore that day for the first time. Felicity was about to reply, “I’m not Miss Rodgers,” and she went so far as to turn up her face to him for the purpose, when he added, “I’ve been hoping to meet you. I’ve heard of your beauty long ago, though I only come to Taverham to visit my aunt.”

Felicity said nothing. They walked slowly along the road together without speaking another word. It was evident that her new friend had never seen either her or Miss Rodgers. This Rita Rodgers was known as the beauty of Taverham. She was twenty-five years old, while Felicity was just nineteen, and of no repute as yet, though she undoubtedly could boast of much. Had the young man, Justin Metcalfe, been told that he had not met the famed beauty, he would have apologized for his mistake and left her side. But Felicity had already lost her heart to him at first glance.

That is how it all began. They spent the day together, both being somewhat young and impulsive, social forms were not scrupulously attended to. In the midst of her happiness, though, Felicity’s conscience was inflicted with guilt at not having yet told him of his mistake. It was true that he had not more than once or twice called her by Miss Rodgers’s name since the first greeting, but he certainly was still under the impression that she was Rita Rodgers. Yet she thought that though he had been led to her by another’s name, it was she that he was so rapidly getting to love, and Felicity’s feminine insight suggested blissfully to her that the face belonging to the name would after this encounter have no power to drag him away from the face of that day’s romance.

“This has been a charming experience to me, Miss Rodgers,” Justin said, at the end of the day, sitting side by side in a cinema. “Accidental meetings have a way of making themselves pleasant.”

It was absolutely necessary to confess this time, though all her happiness was at once destroyed.

“I’m not really Miss Rodgers!” she stammered.

“What? Not Rita Rodgers?” he exclaimed, in surprise.

“Forgive me, Mr. Metcalfe, and I’ve wanted to tell you of your mistake all day, but I couldn’t. I know it is so wicked and wrong of me! I’m only Felicity Sims.”

“But why couldn’t you tell me?”

“Because I was afraid that if I did you would go away from me and not care for me anymore.”

The young woman being close, the cinema being dark, and Justin’s feelings being rather warm, he could not for his life avoid kissing her there and then.

“Well,” he said, “it doesn’t matter. You are yourself anyhow. It is you I like, and nobody else in the world, not the name. But, you know, I was really looking for Miss Rodgers this morning. My aunt told me she’d be a great wife and her father would set me up in business.”

At the end of the movie as they left the cinema another female figure also walked out of the door, and glided away.

“Who is that?” asked Justin to Felicity.

“That’s Miss Rodgers,” said Felicity, horrified. “She’s heard it all. What shall I do, what shall I do?”

“Never mind it a bit,” said Justin and put his arm around her.

Her father’s house stood beside the village’s main road, from which it was separated by a stream, the latter forming also the boundary of the garden and orchard on that side. Outside the young man and the young woman stood talking together. Soon they moved a little way apart, and then it was apparent that their hands were joined. In receding one from the other they began to swing their arms gently backward and forward between them.

“Stay with me a while, Felicity, since I’m leaving for London tomorrow,” he said. “I don’t like parting just now. You know your father will not object.”

“He doesn’t object because he knows nothing to object to,” she whispered. And they both then saw the figure of the father, who could be seen moving about inside the small house.

“It’s nothing so fearful to contemplate,” he said. “As soon as I’ve saved a bit of money I will come back and marry you.”

“I hope you will.”

“But aren’t you glad I’m going? It is better to do well in London than badly here. Say you are glad, dearest. It will fortify me when I’m gone.”

“I’m glad,” she murmured faintly. “I mean I’m glad in my mind. I don’t think that in my heart I’m glad.”

Then the parting scene began, in the dark, under the heavy-headed trees which shut out sky and stars. “Perhaps you may come to London before the spring, Felicity.”

“I may, but I don’t think I shall.”

Spring came and Justin Metcalfe had not been able to save any money and in desperation he decided to leave England to make his fortune in South Africa. Even though Felicity was heartbroken, his letter full of devotion to their shared future, made her make up her mind to the inevitable in a way which would have done honor to an older head. She fixed her happiness with a firm hope on that sunlit future, far away, yet nearing. Circumstances combined to hinder another meeting between them before his departure.

Meanwhile, as the young woman grew older, the woman whose name she had once stolen for a day grew more of an old maid, and showed symptoms of fading. One day Felicity’s father, who, though still a man in the prime of his life was a widower with three children, to whom she acted the part of eldest sister, told Felicity that Rita Rodgers was about to become his second wife.

“Well,” thought Felicity, “what an end for a famous beauty!”

Felicity knew that this step would produce many changes in the small household, and the idea of having as mother the woman to whom she was in some sense indebted for a lover, affected Felicity with dread. Yet nothing had ever been spoken between the two women to show that Rita had heard, much less resented what the younger woman had done.

On a certain day Blake Whitney called. He was of the same family as Rita, though their relationship was distant. He was a rich man according to the standards of the village. He was a bachelor, and full of a boyish happiness rare in one of his years, being forty-six. That day his business with Mr. Sims concerned a loan.

It happened that at the hour of Mr. Whitney’s visit Felicity was feeding the ducks at the stream. She was quite unconscious of the older man’s presence near her, and continued feeding the ducks, until she remained quite still, looking at her own reflection on the water. The stream, though gliding slowly, was yet so smooth that the gentleman could see her pouting mouth, the little nose, the frizzed hair, the bit of blue ribbon, in duplicate.

“What a pretty woman!” he said to himself. He walked up the margin of the stream, and stood beside her.

“Oh!” said Felicity, starting with surprise. In her flurry she dropped the bread and ran off into the house.

“Hee-hee!” laughed Whitney, walking back to his butcher’s shop, murmuring, “What a nice young thing! Well, to be sure. Yes, a young woman rather indeed, a marriageable woman, come to that.”

The doting older man thought of the young one all that day in a way that the young woman did not think of him. He thought so much about her, that in the evening, instead of going to bed, he walked out by the back door into the moonlight, crossed a field or two, and stood in the lane, looking at the young woman’s house, in the hope of getting a glimpse of the attractive woman inside.

A figure moved within, came nearer, and ascended. The

staircase window was large, and he saw his object of devotion going up with a letter in her hand. This was indeed worth coming for. He feared he was seen by her as well, yet hoped otherwise in the interest of his passion, for she came and drew down the window blind, completely shutting out his gaze. The light vanished from this part, and reappeared in a window a little further on.

The lover drew nearer, this, then, was her bedroom. He rested on his stick, and stared at her window with an amorous face.

“Felicity, I suppose you have heard the news from somebody else by this time?” said her father some two weeks later. “I mean what butcher Whitney has been talking to me about.”

“No, indeed,” said Felicity.

“He wants to marry you, if you be willing.”

“Never!” said Felicity with dismay. “That old man?”

“Old? He’s my age, and very well to do. He’ll make you a comfortable home, and dress you up like a doll, and I’m sure you’ll like that.”

“But I can’t, father! I have my reasons.”

“What reasons?”

“I’ve promised Justin Metcalfe four years ago to marry him.”

“Promised to Justin Metcalfe?”

“Yes, surely you know we write to one another regularly.”

“Well, you’re always scribbling and getting letters from somewhere. Where is this man, Justin Metcalfe now?”

“In South Africa still. And he’ll be coming home for me as soon as he made his fortune.”

“I very much question it. Whitney will marry you at once, he says.”

“No, he will not.”

“Well, I don’t want to force you to do anything against your will, Felicity, but this is how the matter stands. If you will marry Whitney, he offers to clear off our debt to him.”

“But Justin will be richer even than Mr. Whitney,” said Felicity, through her tears.

“Yes, yes. But Justin is not here, nor is he likely to be. How silly you are, child. A bird in the hand is ten times better than ten birds in the sky.”

“But he will come, and soon.”

“I wish to Heaven he would.”

“Now, you promise that, father, don’t you?” she said, brightening. “If he comes with plenty of money before you, he shall marry me, and nobody else.”

“Ay, if he comes. But, Felicity, no nonsense. You’re getting older and it’s about time you start a home of your own. You must be a married woman afore the year ends, and wish us a happy new year on your husband’s arm.”

Nothing definite was said to her again on the matter for some time. The butcher hovered round her, but, knowing the result of the conversation between Felicity and her father, he decided to be patient. But one afternoon he could not avoid saying, “Felicity, when may I speak to you about a serious subject?”

“Next week,” she replied, immediately.

He had not been prepared for such an answer, and it startled him almost as much as it pleased him. Had he known the cause of it his emotions might have been different. Felicity, with all the womanly acumen she was capable of, had written to Justin after the conversation with her father, and told him of the dilemma. At the end of the week his answer, if he replied with his customary punctuality, would be sure to come. Fortified with his letter she thought she could meet the old man. Justin she did not doubt.

Nor had she any reason to. The letter came prompt to the day. It was short, tender, and to the point. Events had shaped themselves so fortunately that he was able to say he would return and marry her before the end of the year. She danced about for joy. Her confidence returned, and it was with a mischievous sense of enjoyment that she thought of how she was duping her persecutors.

Whitney came that very afternoon. He was delighted, and danced almost into the room. So lively was the old boy that Felicity was rather alarmed.

“I only accept you conditionally,” she said anxiously. “That is distinctly understood?”

“Yes, yes,” said the butcher. “I’m not as young as I was, little dear, and beggars mustn’t be choosers. Shall it be the first of January?”

“It will really never be.”

“But if he doesn’t come, it shall be the first of January?”

She slightly nodded her head.

The third of December was the last time she received a letter from Justin. Heavens, how anxious she became as the days went by and no new letter had come from Justin.

Her father was married, and Rita lived in the house. Felicity obtained newspapers, scanned the South African shipping news till her eyes ached, but all to no purpose, for she knew nothing either of route or vessel by which Justin would return. He had mentioned nothing more than the month of his coming.

“In ten days, Felicity,” said the butcher, “there is to be no scene or fuss of any kind. The wedding will be quite private, in consideration of your feelings and wishes. We’ll go to church as if we were taking a morning walk, and nobody will be there to disturb you.” He held up his arm and crossed it with his walking-stick, as if he were playing the fiddle.

“He will come, and then I shan’t be able to marry you, even though I may wish to ever so much,” she said mockingly.

The sixth morning before the end of the year came, the noon, the evening. The fifth day came and vanished. Still no word of Justin.

Then one day she had a sensation of being told to have some breakfast, and dress for her marriage with Mr. Whitney, as she had promised to do. All this she did, and at eleven o’clock she became the wife of the older butcher.

When Felicity was putting on her bonnet in the dark that evening, for she wished not to see herself in the mirror, she heard a knock on the door. Felicity turned. Her father’s wife, Rita, was looking into the room, and Felicity could see she was wearing the blue coat, which had determined her destiny. The sight was almost more than she could bear. If, as seemed likely, this effect was intended, the trick was certainly successful.

“You remember the cinema, Felicity,” Rita said, “and how you made use of my name on that occasion, years ago, now?”

“Yes! Did you hear our talk that night? I always fancied otherwise.”

“I heard it all. It was fun to you. What do you think it was to me, fun, too, to lose the man I loved and had been pursuing for months?”

“Ah, no! You have kept back letters from Justin to me!”

“No, I’ve not done that,” said Rita. “But I did receive a telegram from Justin to you and I informed him you had married a week ago, and that it might cause a scene if he came to the village.”

The bride, though nearly fainting, would not flinch in the presence of her adversary. Stilling her trembling body, she said smiling, “That information is deeply interesting, but does not concern me at all, for I’m my husband’s darling now, you know?” And she glided down stairs to the butcher’s van and her new life.

The town of Norwich was perched on a hill so steep that the tall spire of its church seemed like the peak of a small mountain. Its main street consisted of tall buildings of about five or six levels high with shops on the street level and on the higher levels lived tenants. One of the shops was a butcher’s named Whitney’s. Its owner was a burly man, now of about sixty-five years, who had moved to Norwich about ten years before with his wife. They had no children and lived quietly on the sixth floor above the shop. Opposite to the butcher shop was “The Lord Woodley,” a pub. It was here, at a silver daybreak, that two friends met in the street and spoke, though one was beginning the day and the other finishing it. Spencer Haye was very devout, and was making his way to some austere exercises of contemplation at dawn. Justin Metcalfe was by no means devout, and was sitting in evening dress on the bench outside “The Lord Woodley,” drinking what the philosophic observer was free to regard either as his last glass on Monday or his first on Tuesday. Metcalfe was not particular.

The Metcalfes were one of the very few aristocratic families really dating from the Middle Ages, and their coat of arms had actually seen Jerusa

lem. But it is a great mistake to suppose that such houses stand high in chivalric tradition. Few except the poor preserve traditions. Aristocrats live not in traditions but in the here and now. Like more than one of the really ancient houses, the Metcalfes had rotted in the last two centuries into mere drunkards and destitute dandies. As a young man Metcalfe had the ambition of raising his family’s coat of arms high up again and he had done so by diligently working in the rich mines of South Africa. He had not struck it rich, but he had saved enough to retire to his beloved England and live a comfortable life. Idleness, however, is as kissing the devil’s ear, for soon hard work had been exchanged for hard living. Certainly there was something hardly human about Metcalfe’s pursuit of pleasure, and his chronic resolution not to go home till morning. He was a tall, fine-looking, forty-seven, but with hair still brown. He had a very long moustache, on each side of it a furrow from nostril to jaw, so that a sneer seemed cut into his face. Over his evening clothes he wore a curious pale green coat that looked more like a very bright dressing gown than an overcoat, and on the back of his head was stuck a grey homburg hat.

His friend the baker had yellow hair and elegance, but he was buttoned up to the chin in white, and his face was clean-shaven, red, and a little nervous. He seemed to live for nothing but his bakery and family, but there were some who said that it was a love of delicacies rather than of bread, and that his haunting of the bakery like a ghost was only another and purer form of the almost morbid thirst for beauty which sent his friend running after women and wine. This gossip was mostly an ignorant misunderstanding of his love of solitude. He was at that moment about to enter the bakery next to the butcher’s shop, but stopped and frowned a little as he saw his friend’s beady eyes staring in his direction. On the idea that Metcalfe was interested in the bakery, because he wished a cup of coffee and a sandwich he did not waste any speculations. There only remained the butcher’s shop, and though the butcher was a friendly neighbor, Spencer Haye had heard some scandals about his wife. He flung a suspicious look across to the butcher’s store. Metcalfe stood up laughing to speak to him.

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

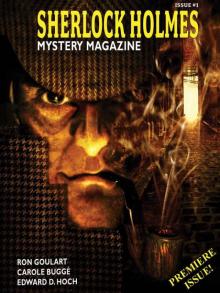

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1