- Home

- Неизвестный

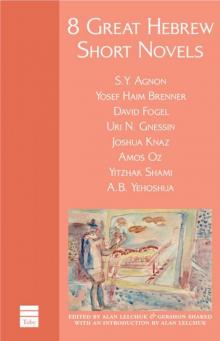

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Read online

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

Alan Lelchuck

Introduction

Bibliographic Note

Uri Nissan Gnessin

Chapter one

Chapter two

Chapter three

Yosef Haim Brenner

Chapter one

Chapter two

Chapter three

Chapter four

Chapter five

Chapter six

Chapter seven

Chapter eight

Chapter nine

Chapter ten

Yitzhak Shami

Chapter one

Chapter two

Chapter three

Chapter four

Chapter five

Chapter six

Chapter seven

Chapter eight

Chapter nine

Chapter ten

S.Y. Agnon

Chapter one

David Fogel

Chapter one

Amos Oz

Chapter one

Chapter two

Chapter three

Chapter four

Chapter five

Chapter six

Chapter seven

Chapter eight

Chapter nine

Chapter ten

Chapter eleven

Chapter twelve

Chapter thirteen

Yehoshua Kenaz

Chapter one

A.B. Yehoshua

Chapter one

About the Editors

Eight Great Hebrew Short Novels

EDITED BY

Alan Lelchuk and Gershon Shaked

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

Alan Lelchuk

The Toby Press

The Toby Press

Third Revised Edition, 2009

The Toby Press llc

POB 8531, New Milford, CT 06776-8531, USA

& POB 2455, London W1A 5WY, England

www.tobypress.com

Copyright © 1983 by Alan Lelchuk and Gershon Shaked

Introduction Copyright © 1983 by Alan Lelchuk

The Toby Press thanks The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature for their kind assistance in the preparation of this revised edition. All translations are © The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature, except as noted below.

SIDEWAYS, by Uri Nissan Gnessin. First published in Hebrew in ha-Z’man, 1905. English translation by Hillel Halkin, copyright © 1983

NERVES, by Yosef Haim Brenner. First published in Hebrew in Shalekhet, Revivim, 1910–11. English translation by Hillel Halkin, copyright © 1983

THE VENGEANCE OF THE FATHERS, by Yitzhak Shami. First published in Hebrew by Mitzpe, 1928. English translation by Richard Flantz, copyright © 1983

IN THE PRIME OF HER LIFE, by S.Y. Agnon. First published in Hebrew in ha-Tekufah, 1922. Translated from the Hebrew by permission of Schocken Publishing House, Ltd. English translation by Gabriel Levin, copyright © 1983, revised © 2004

FACING THE SEA, by David Fogel. First published in Hebrew in Mitzpe: A Yearbook, ed. F. Lachover, 1933, and reprinted in Siman Kriah, 1974. Reprinted by permission of Siman Kriah, English translation by Daniel Silverstone, copyright © 1983 by Daniel Silverstone.

THE HILL OF EVIL COUNSEL, by Amos Oz, copyright © 1976 by Amos Oz and Am Oved Publishers, Ltd. English translation by Nicholas de Lange, copyright © 1978 by Amos Oz. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Inc.

MUSICAL MOMENT, by Yehoshua Kenaz. First published in Hebrew in Siman Kriah, 1978. English translation by Betsy Rosenberg, copyright © 1983, revised © 2004 (based on fifth edition of Musical Moment published in 2001 by Kibbutz Hameuchad/Hasifria Hahadasha)

THE CONTINUING SILENCE OF THE POET, by A.B. Yehoshua. First published in Hebrew in Keshetb, 1966. English translation published in THREE DAYS AND A CHILD, Doubleday, 1970, copyright © 1970, A.B. Yehoshua. English translation by Miriam Arad, copyright © 1970

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

This is a collection of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogues are products of the authors’ imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead is entirely coincidental.

ISBN 978 1 59264 112 3, paperback

A cip catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Typeset in Garamond by KPS

Printed and bound in the United States

In memory of

Philip Rahav,

Ya’akov Shabtai

Contents

Introduction by Alan Lelchuk, xi

Bibliographic Note, xxv

Uri Nissan Gnessin, Sideways, 1

Yosef Haim Brenner, Nerves, 35

Yitzhak Shami, The Vengeance of the Fathers, 79

S.Y. Agnon, In the Prime of her Life, 213

David Fogel, Facing the Sea, 273

Amos Oz, The Hill of Evil Counsel, 335

Yehoshua Kenaz, Musical Moment, 409

A.B. Yehoshua, The Continuing Silence of a Poet, 455

About the Editors, 497

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the services and the support of The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature, and the many kindnesses of Nilli Cohen. Our thanks to other friends who aided this project: Yehuda Melzer, Gabriel Levin, Amos Oz, Menahem Brinker, and A.B. Yehoshua.

Alan Lelchuck

Introduction

These eight short novels were selected primarily for their literary merit, not for their historical place in Hebrew literature, and our emphasis will be on their literary qualities. The assumption, of course, is that they hold up admirably according to the highest standards of world literature. Our aim is to draw attention specifically to these outstanding writers and their distinct contributions in the novella form, without bolstering them, as it were, with that background of politics or sociology that has often been used, if not as apologetics, at least as explanation, for much of Israeli literature. That form of approach, or sentimental parti pris, conceived by well-intentioned friends of Israel and Hebrew literature, has, we fear, in the end done only a disservice to the literature. For it has instilled in many readers the suspicion that Hebrew fiction must be read in the context of its literary youth, against the backdrop of the country’s especially hard-pressed condition. In other words, that Hebrew literature exists with an asterisk alongside it, signifying that it cannot and should not be considered independent of the fact of Israel’s birth over five decades ago. This anthology seeks to correct that false view.

Perhaps another misconception to be dissolved immediately for the general reader is that modern Hebrew literature is a recent phenomenon. Not so. As we can see even from this selection of works, the literature predates the state by at least five decades. Nor was it confined, in place of origin, to that sliver of land alongside the Mediterranean. In fact, most early Hebrew literature was composed in Poland, Russia, Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia… . This geography is significant in literary terms, for it means that many of the artists here—Gnessin, Brenner, Agnon, Fogel—were writing within the vital atmosphere of European literary modernism, and not in provincial isolation. In both theme and style, their works frequently reflect elements of modernism and reveal the dramatic sophistication of these artists.

The strain of sophistication may be viewed in such an unlikely case as that of Uri N. Gn

essin (1879–1913), whose background would suggest a particular insularity and literary innocence. Son of a rabbi in the Ukraine and a student at his father’s yeshiva, Gnessin spent practically his whole life in the shtetl of Potchep, traveling to Palestine for a few months in 1908 to visit his brother and departing with a distaste for the primitive land and crude society. Yet Gnessin, whose major reputation rests basically on four novellas, was anything but a literary provincial, as Sideways indicates. He handled the stream-of-consciousness technique, for example, with easy efficiency at about the same time that Joyce was making it famous. And in several of Gnessin’s themes—the lonely fate of the intellectual, the vacuum of belief after the loss of faith in God, the protagonist who sees what must be changed for his happiness but lacks the will to do anything—Gnessin shows himself to be a self-conscious modern. For Gnessin, despite his narrow background, was much more interested in the soul of man than the social reality of the Jews. To be sure, this reclusive figure who forms one point of the triad that was the base for modern Hebrew literature—the other two being Brenner and Agnon—was more of an aesthete and purist than a cheder boy. Dead at thirty-three of tuberculosis, Gnessin surely needed more years to develop his brand of neo-Romanticism, with its muted but clearly felt eroticism and its poignant portrait of the intellectual’s ennui and ineffectiveness. Yet his four novellas are achievement enough. In certain ways he is the most unique writer in our collection—a sensitive stylist who hardly ever left White Russia yet whose work was suffused with the most advanced techniques and themes of Continental literature. An unfinished writer, he nevertheless exerted a large influence over later Hebrew writers, notably S. Yizhar, who some fifty years later adopted Gnessin’s style in his huge novel of the War of Independence, The Days of Ziklag (1958), and still later, by another two decades, Ya’akov Shabtai, in his important novel Time Continuous (1979).

Gnessin, meanwhile, had his own influences. Indeed, when a character says, in the low-key Sideways, sensitively and skillfully translated by Hillel Halkin, “Why is it so boring around here, it’s always so boring? And we’re bores too,” the reader hears vividly the distant melancholic melodies of a Chekhov play. Or again, when the hero Hagzar is out walking: “The cries of the crows assailed and stunned him, told him with a bitter vengeance that people like him could never take what life offered them, had no business living at all. Ka-a, ka-a, ka-a.” Now we are in the midst of one of Chekhov’s later masterpieces in the novella. Yet certainly Sideways affords its own charm and power, in its careful delineation of the three Baer sisters, the fine cadences and perceptions filling the deliberate style, the social reality of Jewish village life. Of course the story rises or falls with the protagonist, and here Gnessin is entirely successful. Nahum Hagzar is a moving portrait of the stymied scholar and critic, a self-defeating creature of morbidity and asceticism, whose closest literary brother may be George Gissing’s Edwin Reardon of New Grub Street. Hagzar convinces, in all his rueful ruminations and frustrated dreams, and if there is a Chekhov specter hovering about him, a character—and writer—could have a worse ghost.

More obviously modern, in theme anyway, was the work of Gnessin’s dear friend and dear enemy, the renowned Yosef Haim Brenner (1878–1921), a semi-legendary figure of paradox and unpredictability. Brenner had met Gnessin in his father’s yeshiva, and the pair quickly became best friends. Yet later, after Gnessin’s death, Brenner wrote a nasty criticism of his friend and his work, describing their love-hate relationship. In temperament, work, outlook, Brenner was the opposite of his friend. Author, critic, editor, Brenner was also an agricultural laborer, an aggressive journalist, leader of a workers’ movement. A follower of A.D. Gordon, the Tolstoyan Zionist who inspired the kibbutz movement, Brenner was as much activist as intellectual, doer as thinker, and lover of the land as of the written word. He was, too, a severe pessimist with a great zest for life. Unlike Gnessin, Brenner, after a stint in the Czarist army, left the Ukraine never to return, arriving in London for three years in 1905. There he worked as a printer’s compositor while publishing the monthly Hebrew journal Ha-Meorer, which attacked the hollow rhetoric of the political Zionism of that time. In 1908 he traveled to Galicia, in Poland, where he edited the periodical Revivim, and a year later came to Eretz Yisrael to settle for good, working as a laborer and journalist and teaching for a while at the Herzilya Gymnasia. In 1919 he began to edit Ha-Adama, the most influential Hebrew literary journal of its time. In November 1921, warned of immediate danger from rioting Arabs, he refused to leave Jaffa, and was murdered; another abortive ending for a talented life.

Brenner was a passionate Zionist, believing that Palestine was the only place for a Jew to live—“If not here, where?”—but he was also, as Nerves shows almost painfully, a fierce critic of Zionism and Jews. A paradox, a quintessence. Not for Brenner the easy posturing of patriotism, nor the cushion of religious orthodoxy. In a word, he was no comfort then or now, to the professional, religious, or sentimental Jew. Angry, neurotic, scathingly honest and intellectual—he was all of these in the extreme. A thorn to his people, a benefactor for literature: more than a bit like another tortured literary soul. Indeed Dostoyevsky was an acknowledged mentor of Brenner, who translated Crime and Punishment into Hebrew and wrote his own flawed Dostoyevskian novel about an intellectual’s suffering (Breakdown and Bereavement, also published by the Toby Press). But unlike Dostoyevsky, Brenner found life a hell on earth without the prospect of final redemption; for he was a skeptic whose pessimism bordered on downright nihilism. In his work it is this relentless, lacerating vision, embodied in his wounded protagonists, which energizes the fiction and imbues it with an unmistakable, powerful voice.

In Nerves we see many of the Brenner elements fused in the ironic monologue of the European immigrant accompanying a family he has adopted en route to the new land of Palestine, even as he knows beforehand that the journey is one of futility and ultimate despair. In his bitter, caustic remarks about the Jewish people and their destination, the anti hero protagonist displays an anti-sentimentalism that is harshly effective. In his virulent report, the enemy is the sacred and the pious, from landscape and Beauty to Jews and spiritual redemption. Nothing is sacred, in short, and everything and everyone are subject to criticism. There is an underlying anger in Brenner, probably dating back to his profound hatred of his father; and it is neither diluted nor sublimated in his adulthood. This anger is itself a drama, one in which intelligence acts perversely and will nastily; in this Brenner is a forerunner of the great French master Céline. From Dostoyevsky to Brenner to Céline, there runs a continuous line of authorial spite. And if there is no escape for the reader from that scathing drama and vision, there is at least the authentic power of the negative erupting. Not comfort for the reader, or for himself, but truth and turmoil of some sort, are Brenner’s credo, and accomplishment.

Of all the writers in our collection, Yitzhak Shami (1888–1949) is probably the least known and read today. An obscure writer all his life, Shami was a Sephardic Jew from Hebron who taught high school in Palestine, Damascus, and Bulgaria before finally settling to teach in Haifa. His published work is slender, a collection of nine stories and two novellas, written primarily in the 1920s, but they are singular in depicting Jewish-Arab and Arab life. No other Jewish writer understood so well or described so authentically the Arab mind and way as Shami, himself from a Syrian family and as fluent in Arabic and Arab customs as he was in Hebrew and Jewish customs. Not a modernist in any sense, Shami is more old-fashioned, more nineteenth-century, depending on plot and character, atmosphere and incident, for his art. But a genuine art it is. Perhaps no other tale here is quite so riveting, once the story gets going, as that of the local Arab chieftain who falls from honor because of an early misdeed and becomes an outcast and dervish, falling through drugs into hallucinations and his inevitable end. Clearly we are in the hands of a master storyteller, and not a note rings false in this harrowing depiction of the Arab code of honor and prestige,

a code as precise and exacting in its rules and consequences as any Jamesian code of manners and morals.

As an artist Shami is an authentic primitive, like Rousseau in painting; he is a writer dramatizing the exotic and apparently naive by means of close observation of native textures, relying more on external deed than on psychological intrusion to reveal state of mind. The Vengeance of the Fathers is a tour de force of the literary imagination, in the mode of Faulkner in Red Leaves or Tolstoy in Hadji Murad. These three tales—of an Arab leader, an American Indian, and a Tartar chieftain—are triumphs of authorial control in describing the primitive character and temperament without imposing a Western system of values, and in recreating a foreign world without condescending to it or romanticizing it. But more than Faulkner or Tolstoy, probably, Shami knew his material from the inside, having been surrounded all his life by Arabs—more at home with the pipes of hashish, which he was supposed to have imbibed regularly, than with Western intellectual salons or Zionist debates. The Vengeance of the Fathers is a small classical masterpiece, dealing with the traditional rise and fall of the tragic hero. It is a novella unique in Hebrew literature, executed with striking narrative pace and governed by solid knowledge. Reading it, one is immediately dispatched to a distant theater of exotic games and dress, actions and dialogue, which are sensuously detailed and alive. If the first fifty pages of this epic tale read slowly, filled as they are with the necessary background of local customs and values, the reader should bear with it, for the fruits are worth the wait. Once the plot begins, the story is borne forward with skillful sweep and careening inevitability. By the time Shami is finished, the reader has encountered a strange world gradually made familiar; and just as gradually, the particular has become the general, the local universal, the momentary memorable—the surest signs of art.

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

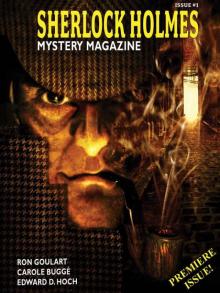

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1