- Home

- Неизвестный

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Page 10

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Read online

Page 10

During this season the fellaheen2 are able to stop work for several weeks. The winter labors are done and the grain is now green and tall and can grow by itself, nourished only by the gentle spring breezes. May Nebi Moussa, whose season this is, protect it from hail or kham-seen.3 True, it’s time to start plowing and sowing for summer crops, and the few fig trees scattered around the ridges need hoeing and weeding, and the olive trees seem to cry out: “Free us from these bonds of earth you heaped around our trunks at the beginning of winter to protect us from the frost. You all wearied of your sheepskins and now wear them inside out, while we stifle here in the heat!” But all this work is not pressing and can be postponed, the last rain will be soon enough, and Nebi Youssef who is buried in Nablus—the peace of Allah be with him—presides over the last rain and its fertility and blessing. It will be worthwhile to visit his tomb, light a candle, and chant the Friday prayers in his mosque when his holy flag is carried out, to be taken to the Mo’ssam.

Only the frivolous—the curse of Allah upon them!—the young renegades who live in the Sahal,4 near the Jewish settlements, where they work as hired hands—only they have begun to reject the old tradition and to scoff at the sanctity of this pilgrimage. True, they may follow the Sanjak,5 as it leaves the shrine, but then they slip away, returning to work the very same day. It is murmured, in the mosques and at the town gates, that they openly deny that the tomb is Nebi Moussa’s, and even argue, as the Jews teach, that the Prophet never crossed the Jordan. But who is so foolish as to believe such inanities? There are idiots of all kinds in the world, idolaters and fire-worshippers who deny the mission of the Prophet. Nor are all those who live in Nablus wholly pious. The effendis 6 and estate-owners—many of them like their alcohol, and eat in secret on the fast days of the blessed Ramadhan.7 No redemption for such as they—they will pay the penalty. Not all the terrors of hell shall purify them of their defilement…

Those of the coastal plain—the Prophet will surely forgive them their errant ways, and not injure the land on their account. They, after all, have a long way to come, and to do double work, to till their own plots as well as the fields and orchards of the Jews. The Jewish Hawadjas 8 don’t even pick their own legumes: they come to the villages and offer high wages for a day’s work, and even give away the gleanings. Any wonder then, that some villagers sell their souls to the devil and neglect the holy day? The Sahal-dwellers are shrewd calculators. Sharp, cunning bargainers. For them each day has its price. A full pilgrimage takes at least ten working days. Ten rials 9 is a considerable amount of money, not to be thrown away in the streets. And if they don’t go they can profit from the Jewish and Christian holy days, Passover and Easter, which fall while most of the fellaheen are traveling to distant places. Their womenfolk bring curds, whey, sour cream, eggs, and vegetables to town, sell the spring blessings at a good price, and return home with heavy bundles of coins in their sleeves and bodices. The men pick up the dinars by the handful, stuff them into jars, and bury them deep in the earth. When they have stored away enough, they open them all, pay for another wife, divorcing one wife and marrying another, or even kill an enemy and pay out the blood money. And finally they also make the pilgrimage to the grave of the Prophet in Mecca,10 drink the holy and purifying Zamzam11 water, don a broad white shawl, and return home, each a perfect hadj 12 who has purchased his world forever.

But the hill-dwellers can confidently leave their homes and meager farms to the children and the old folk, and go off to join the celebrants. A week of little work brings in no earnings. When the work season ends in the hills the fellah has little to do. Many loaf around idly even when work is available. In the hills there is no call for working hands, and those who go off looking for work in the nearby town generally don’t even earn enough to pay the price of a pitta13 and a night’s lodging at a Khan.14 In bad times, when money is scarce and all sorts of creditors and tithe collectors descend on the fellah’s neck to suck his very blood and marrow even before his grain is ripe, the best thing is to flee to the hills and hide until the storm passes. The mukhtars 15 and the sheikhs 16 will know their jobs, and will turn the creditors away with a curt “Go, and return when blessings descend again.”

The pilgrimage to the Mo’ssam and back involves no great expense, praised be the Creator! Every believer whose heart is whole with Allah and his saints can afford it. If Allah has blessed him with beasts he can delight himself and the rest of his household. There is no lack of fodder for the donkeys and the camels: everything is green everywhere—the edges of the fields beside the fences, and the rocky hillsides, are all covered with grass and thistle, rich, juicy, and fattening. The camels chomp it all up lustily, more nourished by it than by the handfuls of hay or dried beans they had been fed on during the winter. Nor are provisions for people necessary. The blessings are abundant, and the wakfs 17 of Nebi Moussa, Nebi Dawoud, and Ibrahim Al-Khalil and of all the other prophets provide for the pilgrims, whether rich or poor. In every town and village through which they pass, the pilgrims find laid out for them troughs and tubs full of rice and curds, colored with saffron and bubbling in boiled butter, food that melts in the mouth. Every grain is separate, like the golden pine nuts with which they are garnished. Notables and paupers alike plunge their hands into the mixture, roll it into little balls between their fingers, and eat to satiety. The glutton and the very poor fill their bowls and jars as well, and the greedy, quite shameless, even pour some into the folds of their garments. Whole sheep simmer in huge pots, and anyone who reaches out a hand can get some. True, swearing and blows, quarrels and fistfights, are everyday occurrences beside the fleshpots and water jars, and occasionally conclude in bloodshed and stabbings. For this reason, many of the wiser pilgrims forego the free meat and rice, so as to keep away from these lovers of strife. They prefer to reach their destination a day or two earlier or later. But who would be so foolish as to miss out on the pilgrimage because of such trivial annoyances? After all, is it to be expected that such a large host of armed men, many of them young and hot-blooded, could travel together such a long way without a stick being raised or dagger drawn almost of their own accord, out of sheer habit?

Actually they’re just big happy children, all excited about making this pilgrimage together and about meeting their brethren from near and far, from Jerusalem and Hebron, from the Negev and the North and the East. Like children they kick and scratch at each other over nothing, simply in fun and mischief. Mostly it all depends on the leaders of the processions, the flag-masters, who are also the sheikhs of the young men. If these show a strong hand, and if their eyes take in everything and hold all their wild and hotheaded young men in tow, if their ears are sharp and can distinguish from afar between fervent song and screams of pain calling for help from kinsmen or neighbors, if they’re always ready to spur their horses into a gallop quickly enough to separate the fighters in time—then you may be sure that with the help of God and his prophets the caravan will continue on its way according to plan. The swords will return to their sheaths, the raised stones will be thrown away, the angry eyes will smile again in reconciliation, and the stragglers will catch up with the caravan. The dispersed circles will reunite, enclosing the troublemakers as in iron rings, all feet will step out more forcefully, a mighty song will burst from their mouths, and even the hills around them will respond, carrying the song from man to man in a powerful echo.

The leaders of the young men—if the devil, the enemy of all the faithful believers (may Allah blacken his face!) does not sow the seeds of discord, jealousy, and competition among them—can make the journey much easier. Upon them depend the splendor and glory of the Mo’ssam. Their good name will attract or repel streams of pilgrims, and although they are elected by the sons of the most powerful esteemed town families, who can control the flags and the wakfs, the fellaheen may either recognize their authority and follow their banner or break up into small groups and, like herds without a shepherd, celebrate the feast by themselves.

&nbs

p; And since so much responsibility rests on the flag-master, not many are willing to take on this office, which besides being a headache and trouble, also involves great expense. The flag-master is expected to supply whatever provisions the pilgrims of his town lack, out of his own pocket. He must also bring to Nebi Moussa gifts that will redound to his honor and that of the flag he bears. From the day the pilgrimage is officially proclaimed, one week before the journey begins, his house must be wide open to the many visitors who come, from dawn to midnight, to congratulate him on his appointment and to consult with him about arrangements for the pilgrimage.

By the banquets and feasts he provides, by his concern and his welcome, the visitors will judge him. If they find him generous, if he succeeds in winning their hearts, they will return his abundance: they will accept his authority and assist him in his task.

In our days it is hard to find devoted nobles who are ready to give their all for the will of Allah and His prophets. Year after year, on Proclamation Day, the young men have to tramp from street to street, from house to house, carrying the flag of Nebi Youssef and singing as they go, in search of a valiant young man who will consent to be their leader. Only after much coaxing, many promises, and much anger do they finally succeed in catching someone.

Nimmer Abu Il-Shawarab was the only man in Nablus who scrupulously observed the customs of the fathers. A courageous and generous man, devoted since childhood to the prophets and the saints, on the upkeep of whose tombs he had spent much gold. The treasurers of the mosques could tell many stories of his generosity and charity. All the young men of Nablus would have responded to his call, despite his hot temper and reputation as a proud, angry man who insisted on obedience and brooked no opposition. His excitability and stubbornness often got him into serious conflicts and unpleasant situations, from which he managed to extricate himself only with the help of police officers who were among his many devoted friends, and of his family’s connections with the authorities in Nablus and Jerusalem. Once he knocked a Bedouin sheikh off his horse for riding through a street without calling out the customary warnings “Your back… .Your face… .

Watch out!”

Once he almost broke the ribs of the water-carrier for spilling some water onto his shoes and clothes. And once he had thrown the cadi’s 18 white headdress to the ground in public, trampling it with his foot and cursing him and all those who had appointed him cadi. Yet despite these traits he was respected by all, and admired for the way he stood up for the deprived, the poor, and the orphaned, and for not currying favor with anyone. It was only because they loved him and wanted to spare him having to spend more than he could afford that the young men passed him by each year in their selection of a flag-master, and informed him of their choice only after the event.

On this Friday morning the young men marched through the Nablus market, singing lustily, with the flag of Nebi Youssef fluttering before them. The procession halted in front of the shop of Hadj Derwish, seller of silks. The flag-bearer stepped out of the circle, ceremoniously approached the shop with measured gait, waved the flag before the entrance several times, extended it and said:

“Together with Allah and Mohammed His Messenger, may your esteemed person carry the banner of Nebi Youssef son of Yakub son of Ibrahim Al-Khalil the Merciful, the glory of the son of Amram!”19

Hadj Derwish’s face turned pale with alarm. In his bewilderment he stammered out several words. For a long while he continued sitting cross-legged on his rug, holding the mouthpiece of his nargilleh 20 in his trembling fingers, unable to bring it to his lips. He looked like an animal at bay looking for a means of escape. Finally he recovered a little and rose. A flap of his abbayeh 21 overturned the nargilleh, scattering the red-hot coals. Then he searched for some time among his rolls of silk and drew out a brightly colored kerchief. He bowed to the flag and tied the scarf around the pole as a sign of refusal. Then he turned his face away like a man who has done his duty, lowered his eyes, and became wholly absorbed in gathering up the remains of the charred tobacco.

The flag-bearer, adamant, refused to accept this answer, and waved his flag again. At that moment his arm was seized, and remained raised in the air, motionless. Abu Il-Shawarab had broken through the circle. He grasped the flag, hastily untied the silk kerchief, threw it in Hadj Derwish’s face, and yelled:

“Shame on such generosity! Go home, my friends! I shall carry your flag! And tonight we feast!”

Abd Al-Razek the Fat, whose legs were as thick and solid as an elephant’s and his shoulders as broad as the beam of the olive press he sometimes turned with his donkey, threw his body about so violently that his black abbayeh slipped off and fell to the ground. He approached Abu Il-Shawarab, kissed him on both shoulders, pounded him affectionately on the back, and exclaimed loudly:

“May you live long among us, O Abu Il-Shawarab! Blessed are they who do good in this world and the next. By Allah, you are worthy to carry the flag! Thrust forth your arm!”

He clapped powerfully on Nimmer’s hand, and all the young men acclaimed the choice. Many heads turned to cheer him, and the roar of their voices and merry hand clapping flooded the street. Arms reached out to him, embracing him and slapping his back and hoisting him up onto the shoulders of the crowd. They refused to let him down, despite his objections and pleas. Singing and carousing, they carried him through the Street of the Leather Workers, and then through the Street of the Confectioners, who filled their hands with sweetmeats and threw them over the heads of the cheering throng. Many of them hurriedly took their pots off the fires, spread a sack over the entrance to their shops, and joined in raucously with the merrymakers. As they advanced, they were joined by more participants: fellaheen who had come to town for the Friday prayers, Bedouin in town for market day, blind men, children, paupers, and curious idlers. A shepherd who had been driving his lambs to the Friday market herded them all into the first khan he came to and ran to catch up with the revelers. When he reached them, he drew out a flute and stuck it in his mouth. His cheeks expanded, and from the reed came a stream of thin, sweet notes, like the chirruping of the first birds at dawn. These flute sounds, when poured out among the hills and waterbeds always made the calves dance and the kids skip over cliffs and stones to gather around the shepherd. Here they had the same effect. Sleeves were rolled up, trouser sashes bound, and soon a long line of dancing men, with hands thrust into their neighbor’s belts, were raising their feet in a wild dance.

Abd El-Kadr the potter, whose legs were agile from constant work at his wheel, really showed his mettle this day, and led the dancers. He stamped both feet down with all his might, twisted them around, lifted them both with a sudden leap and a yell, and brought them down to earth again, now landing on his toes and now on his heels. Behind the crowd came the vendor of suss,22 with his large jar of sweet drink tied to his back. With one hand he jangled the copper trays above his head ring, trying to attract the attention of Abu Il-Shawarab who, mounted on the shoulders of Abd Al-Razek, waved a red kerchief above his head to spur on the dancers; with his other hand he opened and closed the tap on his jar, giving out free drinks. With every glass he poured he roared: “To the honor of Sheikh Il-Shawarab “and the glorious flag!”

When the burning sun began to send beads of sweat pouring down their faces and backs from dancing the debka,23 in which all the limbs take part, the men began to increase the tempo even more until the dance reached a furious pitch in the square before the mosque. Here they began to disperse, and hurried off to the wells to bathe in preparation for the Friday prayers.

In this way the young men of Nablus celebrated the election of Abu Il-Shawarab as their sheikh and flag-master.

Notes

1. The festival of pilgrimage to the tomb of Nebi Moussa (the Prophet Moses).

2. Peasants.

3. Hot east wind bringing a heat wave lasting up to a week.

4. The coastal plain.

5. The holy flag.

6. Officials, or people o

f high position.

7. Month of fasting during which eating is prohibited during the daytime.

8. Masters.

9. A coin about 20 grams.

10. The grave of the Prophet Mohammed, in Medina. In Mecca there is the Ka’aba, the holy rock, which pilgrims visit. Such pilgrimages conclude with prostrations at the tomb in Medina.

11. The waters of the Zamzam: the holy spring in Mecca to which healing powers are attributed.

12. A Moslem who has made the pilgrimage to Mecca.

13. A flat cake of bread.

14. Hostelry.

15. Officials appointed by the authorities.

16. Elders, respected sages.

17. Religious foundations, whose revenues maintain the place. Holy to the respective

prophets (in this case Moses, David, Abraham).

18. Judge.

19. Joseph son of Jacob son of Abraham. The son of Amram is Moses.

20. Water pipe.

21. Loose outer garment.

22. A sweet soft drink.

23. Arab folk dance.

Chapter two

All that week Nimmer Abu Il-Shawarab was busy day and night with arrangements for the pilgrimage. Visitors streamed to his large house outside the town walls, with the rotting horse’s skull stuck over the front gate for luck, and the two huge hands and the seven-pointed candlestick against the evil eye painted on the front wall facing the Jerusalem road. The large empty field beside the house swarmed with people, who bustled and milled about it like busy ants. Coffee sellers, primers of narguillehs, woodcutters, water carriers, and barefoot boys carrying hot coals to and fro in response to an incessant stream of calls. Along the three remaining sides, long tents had been pitched, with rugs and carpets spread inside them for guests to sit on. In the middle of the field, two burning oak trunks leaned on each other, spreading smoke and flames in every direction.

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

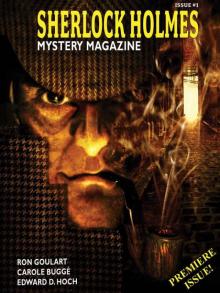

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1