- Home

- Неизвестный

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Page 16

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Read online

Page 16

Notes

1. Ibrahim Al-Khalil—Abraham the Friend (of God) Also a name for the town of Hebron.

2. Religious leader

Chapter five

From here to the shrine of Nebi Moussa was some twenty-five miles. Allah, wanting to placate his favorite, and mitigate the punishment which He had imposed on him in His anger, had promised Moses before he died that He would not leave him alone in the distant desert, to be visited only by heat and dust. He had therefore instructed the faithful, through the mouth of the Prophet Muhammad—peace and prayers be with him!—to attend at his grave every year, during the month he had died in, for seven successive days of feasting and dancing, and had commanded the three most important flags1 to visit him at his shrine with much splendor and ceremony. To make the pilgrimage less of a burden, He had moved the grave several parasangs2 closer to the places of habitation,3 and had made the road leading to it pleasant and easy, so that even old people and children could make the journey without difficulty. Half of it He had set between mountain ridges in a long continuous descent, so that your feet moved forward of their own accord without any effort, and the remainder on the flat and level plain. Marvelous sights greeted the pilgrims at every step. He had gathered pools of cold water from the rains and preserved them in crevices among the rocks, not allowing them to evaporate, to quench the thirst of birds and pilgrims alike. With carpets of grasses and fragrant flowers He had decorated the desolate desert for this brief period, for the sake of those who performed His will, giving them refreshing sights to restore their souls and dissipate their fatigue, inspiring them with renewed vigor.

In the normal course of events, the flag-masters lead their camps on without any unnecessary delays. They complete the journey in less than six hours, hoping to bring their followers to the tall white wall surrounding the great square shrine with its towers and wings and domes by the time the muezzin on the minaret chants the call for evening prayer.

Experienced leaders, who know their people and care for them as a father for his children, have always tried to conclude this part of the pilgrimage in daylight. This way they have time to find resting places inside the buildings for the women and the children and the sick, to see that the distribution of meat and rice is conducted properly according to the quota, and—above all—to spend what remains of the day resting, so that their charges may regain strength before the lighting of the torches4 which will illuminate the desert with dancing flames while celebrants prance around them to the sound of hundreds of drums and other instruments, at the beginning of the noisy and enthusiastic dances which will continue all night long.

As storks train their young to fly, now taking to the heights, screeching and encouraging the fledglings to join them, now returning, to flutter around, support them by their wings, and push them forward, so do the leaders circle around their groups and urge them to walk faster. Now they pass them at a gallop, with gleeful cries; now they mingle among them or drive from behind, occasionally lending a hand with an animal that has collapsed under its load or coaxing stragglers on with all kinds of tricks and proverbs. As they give themselves over completely to joy and fun, the road leaps out to greet them and they arrive with the speed of a dream at their destination.

Since the imaginations of the participants are very active all this time, in years to come they will generally recall only the most prominent or impressive event of the pilgrimage, forgetting all the other trivial details. But the incidents, which precede or cause such an event, are so powerful that they too become engraved in the memory forever. Such was the case this time too. The strange occurrences and amazing sights which attended this pilgrimage determined the atmosphere and created the framework for the awful spectacle that followed, all the parts and links of which were flooded with the red glow of a single flame.

As told by extremely reliable eyewitnesses from among the hadjs and dervishes, seers of things present and future, it appears that while the flag-masters were standing calmly and peacefully side by side with their flags held high, and the Mufti was reciting the holy and venerated opening prayer of the Koran, far down in the valley two crows rose from among the tops of the olive trees. Screeching bitterly, they fell upon each other, gouging and scratching one another with their beaks until large quantities of feathers fell around the flags like autumn leaves. After weaving circles in the air several times, forming a covenant with the agents of hell, they drew tight the ring of enchantment and disaster above the pilgrims’ heads and flew off swiftly and silently, to vanish eastward beyond the mountains.

And from that moment onward the pilgrims were caught in a snare from which there was no escape. The Devil had driven his nose-ring through their nostrils and now led them as he willed, using them as tools for the perpetration of his schemes to make the pilgrimage a failure. His chief agents, disastrously for themselves, were Abu Faris and Abu Il-Shawarab.

After the Mufti and his entourage had left these two, they lost all their self-control, revealing to all present their true faces, which were full of hatred and cold calculation. The passion for honor and revenge burning inside them darkened the light of their reason, dragging and driving them from error to error, to insane and inconsistent actions.

Just as fish darting about around an open net instinctively follow one of their group who swims into it—so did the throngs of pilgrims become entangled in the hellish fabric woven by their leaders, with their whispered and muttered barbs, their contemptuous treatment of each other, the venom that pervaded their movements and comments whenever they passed one another, the fractiousness and contradictions in the commands they gave, and the perversity in their hearts which spread like an epidemic to infect the thousands of sun struck heads of men who followed them with eyes closed as if smitten with blindness, inflaming the blood lust latent in their souls.

Very soon they all lost their way and forgot their objective. The desire to destroy, to injure, to raise riot, became the only driving force in all the camps.

The invisible Devil, who had been working all that day with all the means at his disposal, had now also taken the sun as an ally, using it to close the circle of disaster around the world by bringing to ripeness all the notions of hatred that had not yet fully taken shape.

That terrible day was a day of stifling heat. Even before completing half its journey the sun had lost its luster and taken on that dull silver hue that presages the khamseen. At the fringes of the mountains there were still a few patches of shade here and there where the pilgrims could find some relief, but as soon as they descended into the Jordan Valley they walked into an east wind that blew from the desert as if from the mouth of a white-hot furnace. The wind swept before it gusts of sand and dust, whirling them around as in a devil’s dance. The blazing and charged waves of air stretched the pilgrims’ nerves taut, poured fire into their arteries, and worked up a storm in their hearts.

As beasts of burden plodding along lethargically may suddenly run amok for no reason at all, tearing off their harness, flinging off their loads, kicking and biting at each other—so did the pilgrims clash at every step. Trivial incidents, which during any other pilgrimage would have been passed over or laughed away, developed into unending series of quarrels, which often flared up into a large-scale brawl.

When the shouting and screaming brought the leaders of the two opposing camps running to the scene of the incident, they made no effort to soothe the vexed spirits. Instead, fuming with anger themselves, they either stood there with folded arms like impartial observers or, pretending to be separating the antagonists, misused their status in order to favor their own side. Thus they would grab the arms of someone on the opposing side only if he seemed to have the upper hand, allowing the weaker antagonist, of their own side, to hit him freely.

Prominent among these ugly waves of hatred, bobbing up everywhere, was the suss vendor. On this day there was almost no one who did not become aware of his presence and his strength. His name was an abomination in the Hebro

nite camp. In every cluster that formed around a brawl or a dispute he could be recognized from afar, by his mop of hair that bristled on his head like a hawk’s comb, and by the dark paint around his eyes which had spread with his sweat to smear his cheeks and neck. As long as all he did was to push spectators about or place himself in the middle, shouting abuse at the Hebronites and giving indirect assistance to the Nablusite hotheads, the Hebronites tolerated him and treated him cautiously, careful not to provoke him further. But when his cries of derision grew more numerous than their blows, some of the more daring Hebronites ganged together and cunningly inveigled him into a spot concealed from the sight of his fellows, where they surrounded him and began to rain blows upon him. He, however, did not call out for help. Skillfully swinging his staff—a split pomegranate branch with a rounded head—he drove back his attackers, breaking their ring and making them flee. By the time some Nablusites saw him and rushed to his aid he had completely extricated himself and came striding proudly toward them. Still cursing his attackers violently and calling them by all the known names of abuse, he tore a long strip from the lining of his caftan and bandaged his bleeding forehead with it. Then, straightening his abbayeh and waistband, like a triumphant cock preening his feathers after a hard battle, he stepped forth with head held high into the midst of his townsmen, who stood staring at him in amazement and awe at the bravery he had just displayed.

And so he became the leader of all the Nablusite hotheads who wanted to revenge themselves on the world at large and to terrify everyone they met. As their chief, he devised numerous tricks. He conducted attacks, aroused brawls, and infected all his followers with his own blazing temper and rebellious anger, the result being that the malice and impudence of this wild gang soon broke down all barriers of order and discipline.

In this chaos of quarrels and brawls which burst out time and again with ever greater frequency, the flag-masters found that they no longer had any control over the conduct of the procession, and could not have stopped the rioters even if they had really and truly wanted to. Almost without realizing what was happening, even the more moderate people suddenly seemed to have lost the ground under their feet, and all of them rolled down into a deep abyss of savage strife among brothers, conducted with bared teeth and clenched fists and immeasurable cruelty.

Things went so far that at the well of Maaleh Adumim a fierce struggle took place between Hebronite donkey-drivers who were drawing water for their animals and a group of Nablusites who had come hurrying rowdily after them to try to capture the place for themselves. Yelling fierce battle cries, calling on the name of Allah, the new arrivals snatched up the reins of the drinking animals, beat them, and scattered them in all directions. The Hebronites were not tardy in retaliating, and fell upon their attackers with hoarse cries. Men fought and kicked each other, many of them rolling on the ground, screaming and striking until the water in the troughs was red with their blood. This shameful incident aroused many hearts against the Nablusites, and drew in its train other acts of revenge and infamy.

This year, as in previous years, the proprietors of the Al-Akhmar khan welcomed the flag-masters, and then brought them to a shelter behind the building where they could rest, serving them the banquet that had been waiting for them here since morning.

Abu Il-Shawarab and his officers sat down on the mats around the steaming, fragrant dishes. A little later Abu Faris arrived with his party. They too allowed the khan owner to lead them to the shelter. But when they saw who was seated inside their expressions changed visibly and they quivered with hatred. Without discussing this among themselves, they all turned about at once and strode off, loudly and angrily, the spurs on their boots jangling as they walked. In vain did the bewildered and insulted proprietor plead with them. They denied him the benefit of their presence, and refused to eat or taste anything in his establishment. Glowering, they shook their heads coldly at him, mounted their horses, and commanded their followers to continue on their way and bypass the khan.

When they had traveled far enough so as to no longer hear the din of the Nablus camp, they stopped to rest on the slopes of a reddish hill that was covered with adonis and poppies that bent on their stems with the east wind that blew against them from the desert around Jericho. Here the tired Hebronites lay down to rest, some simply sprawling where they dropped, without moving a limb, while others crawled into the elongated shadows of their camels to find shelter from the blazing sun.

If they were angry when they lay down, they were doubly angered when they were suddenly brought to their feet to see groups of Nablusites who had deliberately left the road and were now rapidly leading their heavily laden animals with shouts through the field where they lay, maliciously disturbing their brief rest. A general pandemonium spread everywhere with nothing to inhibit it, like water pouring down a slope. From all sides came curses, oaths, frightened cries of women and children, and angry voices yelling “Hit them!” “Without mercy!”

Abu Faris and Abu Il-Shawarab did not lift a finger to try to stop the uproar. They circled around the hill slope like wolves seeking prey. In reply to the desperate pleas addressed to them, and to the just demands of the Jerusalemites that they put an end to the dispute, they only shrugged their shoulders and flung back in response: “Let’s see if you can stop this!”

The few policemen accompanying the procession were also powerless to quell the riot. In their attempts to restore order they did not have the courage to burst in among the combatants and use firm measures against them: they contented themselves with spoken appeals, and most of the time ran about helplessly in all directions. Finally their Turkish officer lost patience with the effort, and with a furious expression on his face blew a long blast on his whistle, assembled his policemen, whispered something to them, and then they all galloped off on the road to Jerusalem to request reinforcements.

This simple and daring tactic, together with the untiring efforts of the Jerusalemites, had some effect on the milling crowd, bringing back a modicum of reason. The brawling petered out, and gradually the circles of angry men, which had been whirling about like lakes into which a rain of stones has been hurled, dispersed and quieted down.

All this wrangling had cost them a lot of time. Instead of reaching the mount at the customary time of the evening offering, to pray the third prayer of the day in public assembly, they now arrived at its foot, exhausted and scattered, just before evening, when the setting sun was at the height of a camel and his rider above the horizon. And when they reached the top of the mount, it seemed as if the shrine of Nebi Moussa, with its precariously tall tower, its rounded domes and arched windows, was enveloped in flames from the setting sun, and that the bare hills around it were alight in a bluish-orange hue, like burning sulphur, their long shadows spreading across the plain.

While waiting for the stragglers, the first arrivals moved about wearily, busying themselves with gathering stones and piling them up in little hillocks for markers, and with repairing the many piles that had become scattered since the previous year. Old men and young, fearful of being late for the sunset prayer, hurriedly formed circles and moved aside, while the red glow of before dusk rested on their faces, which were contorted with exhaustion and sorrow. Silently they took off their abbayehs, spread them out on the ground, and stood on them barefooted, with folded arms, in long rows, erect and frozen, like the cliffs and hills beneath them, then bowed and prayed fervently, all bending in unison, like ripe corn when the wind blows through it. When they had completed their whisperings and prostrations they stood up again with a sigh, shaking their heads with concern as they rejoined the many gangs who, forgetting the customs and ignoring the reverence due to their elders, now passed by them, without pausing to wait for them until they had finished their prayer.

For another half hour people kept coming from among the hill-slopes. The camels, sensing that they were soon to arrive and receive their fodder, held their heads erect and joyfully shook the bells hanging around their nec

ks. With no prodding from their owners they moved forward and clambered with broad strides to the top of the last hill that bounds the plain where the mosque stands. Their owners hurried to catch up with them, and everyone advanced more quickly. Going down the hill on the other side, the owners finally caught up with their camels, grabbed their reins, and, pouring out their wrath upon the animals with blows and curses, held them back and forced them to a halt.

According to custom, they were supposed to wait here for the final rite during which the flags were brought into the mosque of Nebi Moussa by the flag-masters at the heads of their parties. So an increasing crowd of people continued to gather here, and one could discern among them many whose faces were filled with the savage anger that had burst out earlier. Their fury and excitement were manifest in their very postures and movements. Of their own accord they divided up into two camps with a large space between them, and a great bustle of movement, marking the final preparations, swept over them like a stormy wave. Now their leaders passed among them with officious speed, moving them excitedly backward and forward, hitting them to get them to form up into columns, the bounds of which each leader determined as he wished. The din increased with the bleating of sheep and goats and the snorting of camels that were also being pushed about. The hundreds of drums and other instruments which pounded out their sounds in total disorder made the earth tremble and startled the horses and the mules, increasing the clamor and filling the hearts of the pilgrims with rage and resentment at the conflicting commands which could in no way be carried out.

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

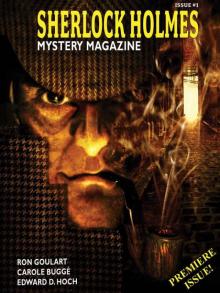

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1