- Home

- Неизвестный

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Page 2

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Read online

Page 2

No one balked at my presence. This was 1977, 1978. The models, so far as I can rely on these memory tendrils I’m chasing, were blasé. These were mostly art students themselves, settled into an easy if boring gig. Likely posing for a group of men and women together was more comfortable, generally, than making a private exhibition for a solitary male, and evenings at Bob and Cynthia’s were convivial. The routine followed the lines of every life-drawing class since publication of Kimon Nicolaides’s The Natural Way to Draw and probably long before it: a series of rapid-fire poses so the artists could loosen with gestural sketches, then five- or ten-minute poses, then a few held long enough for a study—also long enough that the model might pause to stretch or even don a robe and take a five-minute break before resuming. Between poses the artists wandered to see others’ work, and I did this too. Sometimes the models roamed too, in their robes. Other times they were uninterested in the results. I worked with Cray-Pas or gray or colored pencil, or compressed charcoal and, less often, painted in watercolor and gouache. I was less patient than the adults—I was there learning patience, as much as anything—and remember feeling “finished” with studies before the longer poses were done and then watching the clock. Apart from that lapse I worked in absorption, as with all absorbing work since I recall precisely zero from the mental interior of the experience.

What I wasn’t doing—I’d know—was mental slavering. The Tex Avery wolf of sexual voraciousness not only restrained his eyeballs from first swelling like dirigibles and then bursting like loaded cigars, he slept. Any account of the evolutionary “hardwiring” of lust is stuck, I guess, dismissing me now as an outlier, or just a liar. The superextensive actuality of women’s bodies before my eyes was either too much or too little for me to make masturbatory mincemeat of. Both too much and too little: the scrutiny was too much, the context too little. I don’t mean they weren’t sexy bodies. I’d guess they were. But Jonathan-seeing-them wasn’t sexy at all. Even as I recorded with my charcoal or crayon the halo of untrimmed pubic bush and the flesh-braid of mystery that it haloed, I attained a total non-purchase on those bodies as objects of desire. The palace of lust was a site under construction—that’s what I was off doing at night or afternoons, fantasizing about girls I knew who’d never even show me their knees. Then I slavered plenty.

Did I, in my imaginings, substitute for my non-girlfriends’ unconquerable forms the visual stuff I’d gleaned at drawing group? Nope. As much as a T-shirt’s neckline or tube top’s horizon might seem a cruel limit to my wondering gaze, I didn’t want my imagination to supply the pink pebbly fact of aureole and nipple like those I’d examined under bright light for hours at a time. It wasn’t that I found real women’s bodies unappetizing but that I didn’t have any use for them in the absolute visual sphere within which I’d gained access. Much like a person who’s disappointed or confused at seeing the face attached to the voice of a radio personality well known to their ears and then realizes that no face would have seemed any more appropriate, I suspect I didn’t really make mental nudie shots of girls my age. I didn’t picture them undressed; I imagined undressing them and the situations in which such a thing would be imaginable. My eyeballs wanted to be fingertips. I was a romantic.

A romantic teenage boy, that is. My romance encompassed a craving for illicit glimpses, not because I lacked visual information but as rehearsals of transgression and discovery. A craving for craving, especially in the social context of other teenage boys, that mass of horny romantics. But we’re talking about a terrible low point in the history of teenage access to pornography: Everyone’s dad had canceled his Playboy subscription in a simultaneous feminist epiphany a few years before (that everyone’s dad had once subscribed to Playboy was a golden myth; I trust it was halfway true). The Internet was a millennium away. A friend and I were actually excited when we discovered a cache of back issues of Sexology, a black-and-white crypto-scientific pulp magazine, in the plaster and lathe of a ruined brownstone on Wyckoff Street. Pity us. When a couple of snootily gorgeous older teenage girls suddenly moved into the upper duplex of a house on Dean Street, there was some talk among the block’s boys about climbing a nearby tree for a leer, a notion as halcyon-suburban as anything in my childhood. But the London plane trees shading our block had no branches low enough to be climbable, had likely been selected precisely for their resistance to burglars. The point is, I was as thrilled to imagine glimpsing the sisters as any of the other schemers. I could very well have gone off to drawing group the evening of that same day but made no mental conjugation between the desired object and the wasted abundance before me.

Only two uneasy memories bridge this gulf, between the eunuch-child who breezed through a world of live nude models and the hormonal disaster site I was the rest of the time. One glitch was the constant threat or promise that a drawing group model would cancel at the last minute, since tradition had it that one of the circle would volunteer for duty instead. Two of the group’s members were younger women—named, incredibly enough, Hazel and Laurel—for whom I harbored modest but definite boy-to-woman crushes and with whom I may have managed even to be legibly flirtatious. If one evening a model had canceled and either Hazel or Laurel took her clothes off, I’d likely have been pitched headfirst into the chasm of my disassociation. I never faced this outcome. The only substitute model ever to volunteer on my watch was our host, the hairily cherubic Bobby Ramirez. But I would never forget what didn’t happen, who didn’t undress. You may choose to see this as evidence against my assertion that the scene was not a sexual one for me. I choose to see it as certifying proof of my capacity for fantasizing about clothed women who lingered in the periphery of my vision at the exact instant I ignored naked ones in the center of my vision.

The second slippage took place not at drawing group but in my room, with my friend Karl. We were fourteen. Karl and I usually drew superhero comics together, but this afternoon, deep into the porn drought of the 1970s, we drifted into trying to produce our own, doodling fantasy females without the veil of a cape or utility belt. At one point Karl reached an impasse in his attempt to do justice to the naked lady in his mind’s eye and let me analyze the problem. Yes, the nipples were too small, and placed too high, on the gargantuan breasts Karl had conjured. He’d also too much defaulted to the slim, squared-off frame of the supermen we’d been compulsively perfecting. “Do you mind?” I asked. Taking the drawing from Karl, I compacted and softened the torso and widened the hips, gave his fantasy volume and weight, splitting the difference between the unreal ratio and something more persuasive. He’d handed me a teenage boy’s fantasy and I, a teenage boy, passed back a woman, even if one who’d need back surgery in the long run. Karl and I were both, I think, unnerved, and we never returned to this exact pursuit. Our next crack at DIY porn was retrograde and bawdy, a comic called Super-Dick, with images that were barely better than stick figures.

Confessing for the first time my authorship of Super-Dick, I’m flabbergasted, not at the dereliction of parental authority that would traipse nude women past the gaze of a boy still excited to sketch with ballpoint pen a hieroglyphic cock-and-balls in cape and boots and have it catapult into the obliging hairy face of a villain named Pussy-Man, but at the Möbius strip of consciousness that enabled that boy to walk around believing himself a single person instead of two or a hundred. If I’ve bet my life’s work on a suspicion that we live at least as much in our wishes and dreams, our constructions and projections, as we do in any real waking life, the existence of which we can demonstrate by rapping it with our knuckles, perhaps my non-utilization of the live nude models helped me place the bet. How could I ever be astonished to see how we human animals slide into the vicarious at the faintest invitation, leaving vast flaming puddings of the Real uneaten? I did.

My last year at the High School of Music and Art a teacher booked a nude model for us to draw in an advanced drawing class, one consisting only of graduating seniors. By chance this was the last time I’d ever ske

tch from a nude model, though I couldn’t have known it at the time. By implication this was a privilege we seniors had earned after four years of art school: to be treated like adults. Still, there was plenty of nervous joking in the days before, and, when the moment came, the doors and windows were kept carefully shaded against eyes other than those of us in the class. Needless to say, I felt blasé for several reasons, not least my own recent sexual initiation. I’d also begun to reformat myself as a future writer rather than an apprentice artist (at seventeen I’d already been an apprentice artist a long time), and everything to do with my final high school semester felt beneath my serious attention.

Yet ironically, I’ll never forget the model that day. I remember her body when I’ve forgotten the others—had forgotten them, usually, by the time I’d begun spraying fixative on my last drawing of them, before they’d finished dressing. I remember her not because she was either uncannily gorgeous or ugly, or because I experienced some disconcerting arousal, but for an eye-grabbing anatomical feature: the most protuberant clitoris I’d seen, or have since. This wasn’t something I could have found language to explain to my fellow students that day, if I wanted to (I didn’t). The model showed no discomfort with her body. She posed, beneath vile fluorescence, standing atop the wobbling, standard-issue New York City Department of Education tables I’d been around my whole life, the four legs of which never seemed capable of reaching the floor simultaneously, and we thirty-odd teenagers drew her, the whole of us sober, respectfully hushed, a trace bored if you were me, but anyhow living up to the teacher’s expectation. But I do remember thinking: I know and they don’t. (The boys, that would be who I meant.) I remember thinking: They’ll think they’re all that way.

Can a Better Vibrator Inspire an Age of Great American Sex?

Andy Isaacson

The offices of Jimmyjane are above a boarded-up dive bar in San Francisco’s Mission district. There used to be a sign on a now-unmarked side door, until employees grew weary of men showing up in a panic on Valentine’s Day thinking they could buy last-minute gifts there. (They can’t.) The only legacy that remains of the space’s original occupant, an underground lesbian club, is a large fireplace set into the back wall. Porcelain massage candles and ceramic stones, neatly displayed on sleek white shelves alongside the brightly colored vibrators that the company designs, give the space the serene air of a day spa.

Ethan Imboden, the company’s founder, is forty and holds an electrical engineering degree from Johns Hopkins and a master’s in industrial design from Pratt Institute. He has a thin face and blue eyes, and wears a pair of small hoop earrings beneath brown hair that is often tousled in some fashion. The first time I visited, one April morning, Imboden had on a V-neck sweater, designer jeans and Converse sneakers with the tongues splayed out—an aesthetic leaning that masks a highly programmatic interior. “I think if you asked my mother she’d probably say I lined up my teddy bears at right angles,” he told me.

Imboden was seated next to a white conference table, reviewing a marketing graphic that Jimmyjane was preparing to email customers before the summer season. Projected onto a wall was an image that promoted three of Jimmyjane’s vibrators, superimposed over postcards of iconic destinations—Paris, the Taj Mahal, a Mexican surf beach—with the title: “Meet Jimmyjane’s Mile High Club: The perfect traveling companions for your summer adventures.” The postcard for the Form 2, a vibrator Imboden created with the industrial designer Yves Behar, was pictured alongside the Eiffel Tower with the note: “Bonjour! Thanks to my handy button lock I breezed through my flight without making noise or causing an international incident. See you soon, FORM 2.”

Jimmyjane’s conceit is to presuppose a world in which there is no hesitation around sex toys. Placing its products on familiar cultural ground has a normalizing effect, Imboden believes, and comparing a vibrator to a lifestyle accessory someone might pack into their carry-on luggage next to an iPad shifts people’s perceptions about where these objects fit into their lives. Jimmyjane products have been sold in places like C.O. Bigelow, the New York apothecary, Sephora, W Hotels, and even Drugstore.com. Insinuating beautifully designed and thoughtfully engineered sex toys into the mainstream consumer landscape could push Americans into more comfortable territory around sex in general. Jimmyjane hopes to achieve this without treading too firmly on mainstream sensibilities. “Not everyone sits in a conference room and talks about vibrators, dildos, anal sex, clitorises—and we do,” Imboden explained. “It’s important for us to remain a part of the mainstream culture and sensitive to how normal people discuss or don’t discuss these subjects.”

Ten years ago, walking into the annual sex toy industry show for the first time, Imboden was startled by the objects he encountered. He had developed DNA sequencers for government scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and more recently he had left a job designing consumer products—cell phones and electric toothbrushes—for companies like Motorola and Colgate, work he found dispiriting. “It was imminently clear to me that I was creating a huge amount of landfill,” Imboden told me. “I wanted no part of it.” He struck out on his own, and found himself approached by a potential client about designing a sex product.

The floor of the Adult Novelty Manufacturers Expo, held that year on the windowless ground level of the Sheraton in Universal City, California, flaunted fated landfill of a different sort: a gaudy display of “severed anatomy, goofy animals, and penis-pump flashing-lights kind of stuff,” Imboden recalled. These tawdry novelties dominate the $1.3 billion-a-year American sex toy market. They are the output of a small but cliquish old boys’ network of companies you’ve probably never heard of, even if you have given business to them. One of these, Doc Johnson, was named as a mocking tribute to President Lyndon B. Johnson, whose justice department in the 1960s tried in vain to prosecute the late pornographer Reuben Sturman, the industry’s notorious founding father. Sturman invented the peep show booth, and built a formidable empire of adult bookstores that for decades constituted the shadowy domain where such products were sold, usually to men.

Imboden was inspired. “As soon as I saw past the fact that in front of me happened to be two penises fused together at the base, I realized that I was looking at the only category of consumer product that had yet to be touched by design,” Imboden said. “It’s as if the only food that had been available was in the candy aisle, like Dum Dums and Twizzlers, where it’s really just about a marketing concept and a quick rush and very little emphasis on nourishment and real enjoyment. The category had been isolated by the taboo that surrounded it. I figured, I can transcend that.”

At dinner parties in San Francisco, where he lives, Imboden found that mentioning sex toys unleashed conversations that appeared to have been only awaiting permission. “Suddenly I was at the nexus of everybody’s thoughts and aspirations of sexuality,” he said. “Suddenly it was okay for anyone to talk to me about it.” It occurred to Imboden that the people who buy sex toys are not some other group of people. They are among the half of all Americans who, according to a recent Indiana University study, report having used a vibrator. They are people, like those waiting outside Apple stores for the newest iPhone model, who typically surround themselves with brands that reinforce a self-concept. They spend money on quality products, and care about the safety of those products. Yet, for the very products they use most intimately—arguably the ones whose quality and safety people should care most about—they were buying gimmicky items of questionable integrity. It’s just that people had never come to expect or demand anything different—silenced by society’s “shame tax on sexuality,” as one sex toy retailer put it to me. And few alternatives existed.

Jean-Michel Valette, the chairman of Peet’s Coffee, who would later join Jimmyjane’s Board of Directors, told me: “I had thought the opportunities for really transforming significant consumer categories had all been done. Starbucks had done it in coffee. Select Comfort had done it in beds. Boston Beers”—t

he makers of Samuel Adams—“had done it in beer. And here was one that was right under everyone’s nose.”

Jimmyjane’s success has inspired a growing class of design-conscious companies—including Minna, Nomi Tang and Je Joue—that are beginning to clean up an unscrupulous industry long cloaked by American discomfort around sex. LELO, a Swedish brand founded by industrial designers, creates upmarket products with names—Gigi, Ina, Nea—that sound like feminized IKEA furniture. (Try Gigi on the SVELVIK bed!) OhM-iBod, a line of vibrators created by a woman who once worked in Apple’s product marketing department, synchronize rhythmically with iPods, iPads, iPhones and other smartphones.

I asked Imboden what qualified him to design a vibrator, a device primarily intended for female pleasure. Imboden said he considers himself “decidedly heterosexual,” but also “universally perceptive,” and he suspects that the formative childhood years he spent living with his mother and older sister, after his father died of cancer when he was two, may have nurtured within him a certain empathy for the opposite sex. (His father had also been an engineer, also worked at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, and ended up starting a dressmaking company called Foxy Lady.) “Ethan has an intellectual curiosity and an emotional maturity that doesn’t stop him from exploring something that a man ‘shouldn’t,’” said Lisa Berman, Jimmyjane’s C.E.O., who came from The Limited and Guess and is among the company’s all-female executive team. “He is a real purist in the way he thinks, not just about engineering and design but the emotional connection that these products might assist in a relationship. He can do that better than anyone that I’ve met.”

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

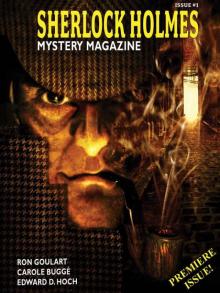

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1