- Home

- Неизвестный

Colossus Page 3

Colossus Read online

Page 3

“As President of the United States of North America, I have to tell you, the people of the world, that as of eight o”clock Eastern Standard Time this morning the defense of the nation, and with it the defense of the free world, has been the responsibility of a machine. As the first citizen of my country, I have delegated my right to take my people to war.

“That decision now rests with Colossus, which is the name of the machine. It is basically an electronic brain, but far more advanced than anything previously built. It is capable of studying intelligence and data fed to it, and on the basis of those facts only—not of emotions—deciding if an attack is about to be launched upon us. If it did decide that an attack was imminent—and by that I mean that an assault was impending and would probably be launched within four hours—Colossus would decide, and act. It controls its own weapons and can select and deliver whatever it considers appropriate.

“Understand that Colossus” decisions are superior to any we humans can make, for it can absorb far more data than is remotely possible for the greatest genius that ever lived. And more important than that, it has no emotions. It knows no fear, no hate, no envy. It cannot act in a sudden fit of temper. Above all, it cannot act at all, so long as there is no threat.

“Fellow humans, we in the USNA now live in the shade, but not the shadow, of Colossus. And indirectly, you do too. May it never see fit to act.”

The President took another sip of water. He was aware that the Tass man, Kyrovitch, was about to speak, but he also saw Prytzkammer motion him to be silent. The rest of the reporters looked dazed. The President was enjoying himself even more than he had expected.

“We of the free world,” he continued, “do not want war. Indeed, we will never fight unless attacked. Now that we have Colossus we have no real need for armed forces except for minor disturbances. It is therefore my intention to reduce the overall strength of our fighting services by seventy-five percent over the next five years. As soon, in fact, as the readjustment can be made.

“Further, we are prepared to show the world how Colossus works—what has been built into it—and to prove to anyone's satisfaction” (he could not help flashing a look at Kyrovitch) “that Colossus is a defensive system. If we can convince the Soviet Bloc that Colossus is solely defensive, and demonstrate that we have no offensive intentions by the virtual disbandment of our Navy and Army and Space forces, relying solely on Colossus to protect us, we may well be along way towards lasting peace and the end of the cold war that has bedeviled us all for so long.”

The President swiveled in his chair to face the correspondents.

“Now, gentlemen, I am prepared to answer any questions you may care to ask. I am not of course, familiar with all the technicalities of this vast work, so I would like to introduce Professor Charles Forbin. He is, I think, the world's leading expert on electronic brains. Certainly no man knows more about Colossus than he does. He has worked on it since the first design study group was set up at Harvard twelve years ago.” He motioned Forbin to stand behind him, and Forbin did so, wearing a slightly stuffed expression.

Mazon was the first to speak.

“It's a little difficult, Mr. President, to grasp the size of what you have just told us. I find it hard to conceive of the essential nature of this Colossus. For instance, can it think?”

“That, Mr. Mazon, is just the sort of question for the Professor here.” The President motioned to Forbin.

Forbin was not only nervous about the potential of Colossus, he was now nervous of the TV camera as well. He reached for his notes, or where they would have been had he been wearing his usual blouse instead of the stiff and uncomfortable lounge suit. He gave up the search, his hands looking lost without some employment.

“Can it think?” Forbin repeated the question, more for his own benefit and to gain time than anything else. “The term 'electronic brain' has always been a popular one for what, really was an arithmetical device which could distinguish between one and two. That is still the basis of all computers. There are a good many computer-type components in Colossus, but the essential core of the machine-complex is infinitely more sophisticated. Just as you can say that the proportions of the Parthenon are a matter of two to one in essence, but the detailing is extremely complex. It's that development which makes all the difference. Colossus really is a 'brain' in a limited sense. It can think in a sort of way, but it has no emotions, and without emotional content, creation is not possible. It could not create, say, a Shakespeare play—or any sort of play for that matter, although as part of its background knowledge we have fed in all the plays—and, given any three consecutive words from anything Shakespeare wrote, or anything a hundred playwrights wrote, Colossus could finish the quotation. Colossus has a vast memory store; it wouldn't be far from wrong to say that it has the total sum of human knowledge at its disposal. On the basis of that background, plus the data continually being fed in, it forms its judgments—just like a human being. Though with the very important difference that it never overlooks a point, is not biased and has no emotions. But think creatively—no.”

Forbin paused and moved so as to address the President. “Sir, with your permission, I would like to demonstrate this emotional point.”

“Certainly, Professor. I am sure we would all be very interested.”

Forbin finally found somewhere to put his hands, stuffing them in the side pockets of his jacket, nautical fashion. He appeared very uncomfortable.

“Colossus is essentially an information-collecting, sorting and evaluating complex, capable of factual decisions and action if necessary. It can evaluate the printed word, speech or visual material. Languages are no difficulty. For warning and test purposes—tests at our end, that is, for there is no teletype inside Colossus to go wrong—we have teletype lines directly to the complex. One is right here, in this office.”

Forbin nodded to Prytzkammer who wheeled forward a dust-sheeted trolley. Forbin removed the sheet, revealing an ordinary teletype machine, rather like an electronic typewriter, with a few extra keys and a large roll of paper mounted at the back of the carriage. The reporters stared at it, mesmerized.

“Now,” said Forbin, “would one of you gentlemen care to name an emotion?”

“Love.” It was Plantain who spoke, his voice devoid of expression.

His Russian colleague frowned. Dugay glanced quizzically at his fellow European.

“Good,” said Forbin. “Love. Now Colossus has a vast knowledge of the subject, but it cannot experience love, nor evaluate emotion. I will confess,” he smiled, “this particular question has not been fed in before, but I'm confident we will get a very lame reply. Still, a question that may be regarded as factual, on the same subject, will produce a very different answer—just because it is a matter of fact, whether it's about an emotion or not.”

He bent over the teletype and clumsily picked out his message with two fingers. It was just two words:

EXPLAIN LOVE

“I have temporarily stored this message here,” he tapped the gray top of the machine, “so that you might all see the message and observe the speed of the answer.” He tore off the strip with the words on it, passed it to Dugay.

“You, sir, as a Frenchman, represent the nation best able to appreciate the complexity of this question.” Forbin's smile robbed his words of any offensive overtones.

Dugay took the slip, read it and smiled back.

“It is, as you say, a honee of a question.” He passed the slip to Kyrovitch who looked at it distastefully and quickly passed it to Plantain, who kept it.

“Right, gentlemen,” Forbin continued. He was beginning to enjoy himself. “Watch. I press the feed-in control—thus.” For half a second nothing happened. Even in that short time the tension in the room became so strong as to be practically tangible. Then the machine chattered briefly. The smile on the President's face had become a fixed mask.

Only Forbin was at ease. Without looking at the answer, he tore off the answer, pas

sed it to Dugay. The Frenchman raised one expressive eyebrow.

“It is certainly a lame answer, Professor.” He reached over Kyrovitch and handed the slip to Plaintain, who obligingly held it up for Camera One. There were just four words.

LOVE IS AN EMOTION

Forbin read the answer on the monitor screen, and smiled at the reporters. “And that is about as good as Colossus can get. But my next question—” once more he bent over the teletype. The President cautiously looked at his watch. Kyrovitch yawned conspicuously.

“I have again held transmission.” Forbin passed his second message to Dugay. “You may think this question cannot be answered accurately. It is—'What is the best written definition of love.' I can tell you how Colossus will tackle this one. It will look up every reference to love on file, and there must be at least tens of thousands. From these it will select those which, in some way, define love, and there will be thousands of those, and all of them will be sorted for the common factors. This work will be done by several sectors of the machine at once and the answers fed to the central control, where the machine synthesizes an answer based upon its researches. This answer will then be compared against all the definitions of love for the one nearest its synthetic answer. This it will do in any language—an Arabic love poem, a Polynesian fertility rite, some reference in an Icelandic saga. When it has found what it regards as the nearest to its synthetic answer, it will check the original,” Forbin leaned forward, clearly regarding his next sentence as important, “and will type out the reference, not the definition itself. It will supply this if wanted, but remember, that was not the question we are asking. If we want to know the exact words, it would be necessary to Say 'Give the best written definition' etc. The final point I want to make before pressing the feed-in button is this. The process I have outlined will be carried out by the machine in five to ten seconds.”

Kyrovitch snorted with disbelief. The rest looked even more dazed than before. Forbin turned to the teletype. “Here we go.

He pressed the feed-in control.

Plaintain whispered something to Dugay round the back of the intervening Russian's neck. Dugay grinned. Kyrovitch simmered gently.

The machine began to chatter.

Mazon, who had been studying his watch intently, looked up and almost shouted, triumphantly, “Seven goddam seconds!”

It was quite unlike any press conference ever held. The President was half out of his chair, leaning over the desk. Camera Two tactfully took a shot of Forbin, bending over the teletype.

Forbin tore the strip off the machine, looked up and spoke in a level voice.

“It says—SHAKESPEARE SONNET CXVI.”

“Follow that,” muttered Mazon.

Kyrovitch did.

“Mr. President, this is no time for tricks, we of the Socialist Soviet. . .”

The President secretly agreed with Kyrovitch, and was glad of his interruption to regain control.

“Gentlemen,” he said, cutting in, “I hope this small demonstration illustrates the point which cannot be overemphasized. Colossus knows about emotion, but cannot experience it. It can never act in fear or hate. This is the most vital point for you to remember.”

The President favored Camera Two with a long direct stare.

“No defensive action will ever be undertaken by the United States of North America out of fear, jealousy, greed or hate.” He would have liked to have stopped the conference on that note, but Kyrovitch was not going to let him get away with that one. Swiftly he broke in on the President's stare.

“You say you feed it information. What sort, and how?” The President was not going to be coy about that one. “Every form of intelligence or information available to our Central Intelligence Agency. Everything, from agents' reports,” he gave Kyrovitch a wolfish smile all to himself, “to newspapers, TV and radio broadcasts, movements of aircraft, troops, ships, satellites, all statistics on harvests, birth rates, rainfall—anything and everything that we think has the remotest bearing on the problem—plus practically anything else that is going.”

Kyrovitch gave a deep-throated growl. “But how is it fed to the, the thing?”

“I was coming to that.” He didn't like to sit answering questions from a Commie reporter, or any other reporter, come to that. “Professor Forbin, you are better qualified to answer. . .”

Forbin nodded and was suddenly conscious of his hands once more. He folded his arms across his chest, but the TV producer's frown and shaking head sent them plunging back into his pockets.

“Feed-in. Yes. Mostly by land-line. All information is converted to electrical impulses, in just the same way that any transmitter—teletype, TV or radio—converts vision or sound into impulses. They are then fed down the line to Colossus, who then stores them in his—its own way. They are not converted back to pictures, letters or figures.”

“Pictures?” queried Mazon.

“Yes. We pass pictures from newspapers or TV or plans of buildings. Anything that can be expressed on a sheet of paper or a flat surface goes down the pipe. I may say, since Colossus is not secret any more, it watches all the major TV programs—Soviet, American, European and so on. Moving pictures were a little tricky, but it works.”

“It sure is a good thing Colossus hasn't got emotions,” said Mazon with feeling.

“Perhaps so,” Forbin smiled. “On the nonvisual side it monitors all the main radio transmissions of the world, civil, military and space-wise. It also reads, in its own way, all the newspapers of the world—even the sports pages.”

“Listening to all that has been said,” Plaintain looked at Forbin, “I have an impression that Colossus is quite large—is that so?”

“Yes, the name is appropriate. I can tell you that it is about the size of a small town of, say, seven to ten thousand people.”

“Are we permitted to know where it is?” said Kyrovitch. Mazon gave a snort of derisive laughter. The President thought it was time he was back center stage.

“Why, certainly, Mr. Kyrovitch. It is located inside the Rocky Mountains. The exact spot will be shown on the maps which you will receive later with the official press handouts.” The President felt much better when he was doing the talking. “As a nation we have carried out some pretty large works. Panama Canal, Grand Coulee Dam, the TVA project—and more recently the Space Reflector Stations, the Moon project, the Trans-ocean oil lines to Europe, not to mention the coast-to-coast air-car roads. I may say the effort required to produce the last three projects together would not be enough to build Colossus. It took three years to dig the hole, even using nuclear digging techniques, and there were another three years needed to line the hole with cement, and to prepare the bare shell to receive the equipment. It is by far the biggest single enterprise undertaken by this nation in all its history.”

“You say, Mr. President,” said Kyrovitch, anxious to flatten proceedings as much as possible, “that the armed forces of this country will be reduced by seventy-five per cent—are the rest guarding Colossus?”

Sucker, thought the President, this will teach you not to lead with your chin.

“No, sir. That twenty-five per cent would, I imagine, be used solely to resist subversion. Colossus certainly does not need them. Of course, there are a good many people engaged at the external ends of the feed lines. For example, if Colossus is to read Pravda,” he smiled once more at Kyrovitch, “or Grimm's Fairy Tales, someone has to present the paper to a scanner. There are practically no other personnel involved. There are no servicing teams—not human ones, anyway. Colossus works alone.”

That shook them, thought the President. It had. Plaintain raised both eyebrows, which was the ultimate in facial expression he ever permitted himself. Dugay's eyebrows merged into one black line, as he wrestled with the implications. Kyrovitch rumbled quietly to himself, clearly at a loss what to say. Mazon beamed uncertainly, like a first-time father presented with quads. M'taka rubbed his fuzzy white pate and wished he had studied science instea

d of the humanities. Dugay spoke first.

“But the control, the maintenance. . .” he stopped, still mentally fumbling.

“Professor,” the President nodded.

“As you may know,” Forbin said, “back before our time electronic equipment was crude and unreliable. They had valves or tubes, which worked after a fashion, but could never be regarded as reliable. Then came transistors, a big advance in many ways—some are still in use—but these too weren't what we would regard as reliable. Then came the semiconductors, the use of laser beams of coherent light and the development of power cells.” Forbin was aware that the President was squirming slightly in his seat. “But I won't go on with the technical details; they will be available to those that want them afterward. Enough to say that we have perfected components and circuits, sealed in blocks which are stable in all conditions, impervious to heat, damp, cold, gas or anything else. As a further safeguard, all circuits are duplicated—in some cases, triplicated. Colossus is capable of tracing its own faults and switching in a new circuit if necessary. Our calculation—confirmed, I may add, by Colossus' own figuring—is that one block circuit in every ten thousand may be expected to fail every four hundred years.”

Kyrovitch bounced to his feet with surprising speed. “Four hundred years!” he roared.

“That's what the man said, buster!” yelled a red-faced Mazon.

“Gentlemen, gentlemen.” The President raised a pacifying hand for silence. The TV producer reached forward and pulled Kyrovitch gently by the back of his jacket. The President looked at the reporters; the Limey would be the one to take the heat out of the situation.

“What was your question, Mr. Plaintain?” He looked inquiringly at the Englishman, who had not asked one.

“Thank you, Mr. President,” Plaintain said gracefully. “I am indeed amazed at what Professor Forbin has just said. If this is the sort of time scale you have in mind, four hundred years to the first fault, how long is it expected that the machine will last?”

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

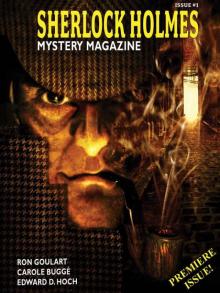

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1