- Home

- Неизвестный

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) Page 3

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) Read online

Page 3

‘That does not happen,’ one of the businessmen said. ‘It’s propaganda.’

Then the men excused themselves politely and left; Maryam was embarrassed.

‘You should not have asked that,’ she remonstrated quietly.

‘But it’s true,’ I said.

She turned her face away, and in a cloud of narghile smoke replied, ‘Syrians cannot bear that we are doing this to each other. Once we had a common enemy – Israel. Now we are each other’s enemy.’

7. The Shabaab

The war had come to Damascus – hit-and-run operations by the opposition; bombings in defence of their minute strongholds. The government, which has tanks and aircraft, kept to the high ground and pummelled opposition fighters from above. The FSA are said to be armed by Qatar, Saudi Arabia and to some extent by the United States, but when you see the fighters – the shabaab, the guys – you see what they need is anti-tank weapons and anti-aircraft guns. They have none. Their weapons are old. Their uniforms are shabby. They fight wearing trainers.

Zabadani, a town close to the Lebanese border on the old smugglers’ route, had once been a tourist attraction but is now empty except for government gunners on the hills and FSA fighters in the centre of town. Before the war, the town was more or less a model community: mainly populated by Sunnis but a friendly place where people were welcomed, and where ethnicity and religion did not matter.

‘There is a feeling of belonging in Zabadani that the regime deprived us of,’ said Mohammed, a young journalist I had met in Beirut who was born and raised in Zabadani, but who had been forced to flee. ‘We felt Syrian. Not any ethnic or religious denomination.’

I crowded into a courtyard of an old building in town, which was protected from shelling on all sides, with a group of fighters on what they counted as the fifty-second day of straight shelling in Zabadani. They did the universal thing soldiers do when they wait for the next attack: drink tea, smoke cigarettes and complain.

‘What did you do in your former life?’ I asked this ragtag bunch.

One was a mason; another a truck driver; another a teacher; another a smuggler. Thirty years ago, the roads from Damascus to Zabadani were infamous for smuggling.

‘You could buy real Lacoste T-shirts, anything, for the cheapest price.’ Everyone laughed. Then there was the sound of machine-gun fire and the smiles disappeared.

At the Zabadani triage hospital, which keeps getting moved because it keeps getting targeted and blown up, the sole doctor was stitching up a soldier who had been hit in a mortar attack. The current hospital location had been a furniture shop and was well hidden in the winding streets of the Old City, which had been taken over by the FSA. As the doctor stitched in the dark, he talked: ‘Both sides feel demoralized now,’ he said. ‘But both sides said after Daraya’ – referring to the massacre – ‘there is no going back.’

The doctor insisted on taking me back to his house and giving me a medical kit for my safe keeping. ‘You need it,’ he said. As I left, his wife gave me three freshly washed pears.

‘The symbol of Zabadani,’ said the doctor. ‘They used to be the sweetest thing.’

There are no templates for war – the only thing that is the same from Vietnam to East Timor to Sierra Leone is the agony it creates. Syria reminds me of Bosnia: the abuse, the torture, the ethnic cleansing and the fighting among former neighbours. And the sorrow of war too is universal – the inevitable end of a life that one knows and holds dear, and the beginning of pain and loss.

War is this: the end of the daily routine – walking children to schools that are now closed; the morning coffee in the same cafe, now empty with shattered glass; the friends and family who have fled to uncertain futures. The constant, gnawing fear in the pit of one’s stomach that the door is going to be kicked in and you will be dragged away.

I returned to Paris after that second trip, and thought often of a small child I met in Homs, with whom I had passed a gentle afternoon. At night, the sniping started and his grandmother began to cry with fear that a foreigner was in the house, and she made me leave in the dark.

I did not blame her. She did not want to die. She did not want to get raided by the Mukhābarāt for harbouring a foreign reporter.

The boy had been inside for some months and he was bored: he missed his friends; he missed the life that had ended for him when the protests began.

For entertainment, he watched, over and over, the single video in the house, Home Alone – like Groundhog Day, waiting for normality to return so he could go out and play, find the school friends who months ago had been sent to Beirut or London or Paris to escape the war, and resume his lessons.

‘When will it end?’ he asked earnestly. For children, there must always be a time sequence, an order, for their stability. I know this as a mother. My son is confused by whether he sleeps at his father’s apartment or his mother’s and who is picking him up from school.

‘And Wednesday is how many days away?’ he always asks me. ‘And Christmas is how many months? And when is summer?’

‘So when is the war over?’ this little boy asked me.

‘Soon,’ I said, knowing that I was lying.

I knelt down and took his tiny face in my hands. ‘I don’t know when, but it will end,’ I said. I kissed his cheek goodbye. ‘Everything is going to be fine.’

GRANTA

* * *

DON’T FALL

IN LOVE

Mohsin Hamid

* * *

So it is worrisome that you, in the late middle of your teenage years, are infatuated with a pretty girl. Her looks would not traditionally have been considered beautiful. No milky complexion, raven tresses, bountiful bosom or soft, moonlike face for her. Her skin is darker than average, her hair and eyes lighter, making all three features a strikingly similar shade of brown. This bestows upon her a smoky quality, as though she has been drawn with charcoal. She is also lean, tall and flat-chested, her breasts the size, as your mother notes dismissively, of two cheap little squashed mangoes.

‘A boy who wants to fuck a thing like that,’ your mother says, ‘just wants to fuck another boy.’

Perhaps. But you are not the pretty girl’s only admirer. In fact, legions of boys your age turn to watch her as she walks by, her jaunty strut sticking out in your neighbourhood like a bikini in a seminary. Maybe it’s a generational thing. You boys, unlike your fathers, have grown up in the city, bombarded by imagery from television and billboards. Excessive fertility is here a liability, not an asset as historically it has been in the countryside, where food was for the most part grown rather than bought, and work could be found even for unskilled pairs of hands, though now there too that time is coming to an end.

Whatever the reason, the pretty girl is the object of much desire, anguish and masturbatory activity. And she seems for her part to have some mild degree of interest in you. You have always been a sturdy fellow, but you are currently impressively fit. This is partly the consequence of a daily regimen of decline feet-on-cot push-ups, hang-from-stair pull-ups, and weighted brick-in-hand crunches and back extensions taught to you by the former competitive bodybuilder, now middle-aged gunman, who lives next door. And it is partly the consequence of your night job as a DVD delivery boy.

Beyond your neighbourhood is a strip of factories, and beyond that is a market at the edge of a more prosperous bit of town. The market is built on a roundabout, and among its shops is a video retailer, dark and dimly lit, barely large enough to accommodate three customers at the same time, with two walls entirely covered in movie posters and a third obscured by a single, moderately packed shelf of DVDs. All sell for the same low price, a mere twofold markup on the retail price of a blank DVD. It goes without saying that they are pirated.

Because of splintering consumer tastes, the proprietor keeps only a hundred or so best-selling titles in stock at any given time. But, recognizing the substantial combined demand for films that each sell just one or two copies a year, he has

established in his back room a dedicated high-speed broadband connection, disc-burning equipment and a photo-quality colour printer. Customers can ask for virtually any film and he will have it dropped off to them the same day.

Which is where you come in. The proprietor has divided his delivery area into two zones. For the first zone, reachable on bicycle within a maximum of fifteen minutes, he has his junior delivery boy, you. For the second zone, parts of the city beyond that, he has his senior delivery boy, a man who zooms through town on his motorcycle. This man’s salary is twice yours, and his tips several times greater, for although your work is more strenuous, a man on a motorcycle is immediately perceived as a higher-end proposition than a boy on a bicycle. Unfair, possibly, but you at least do not have to pay monthly instalments to a viciously scarred and dangerously unforgiving moneylender for your conveyance.

Your shift is six hours long, in the evening from seven to one, its brief periods of intense activity interspersed with lengthy lulls, and because of this you have developed speed as well as stamina. You have also been exposed to a wide range of people, including women, who in the homes of the rich think nothing of meeting you alone at the door, alone, that is, if you do not count their watchful guards and drivers and other outdoor servants, and then asking you questions, often about image and sound quality but also sometimes about whether a movie is good or not. As a result you know the names of actors and directors from all over the world, and what film should be compared with what, even in the cases of actors and directors and films you have not yourself seen, there being only so much off time during your shifts to watch what happens to be playing at the shop.

In the same market works the pretty girl. Her father, a notorious drunk and gambler rarely sighted during the day, sends his wife and daughter out to earn back what he has lost the night before or will lose the night to come. The pretty girl is an assistant in a beauty salon where she carries towels, handles chemicals, brings tea, sweeps hair off the floor and massages the heads, backs, buttocks, thighs and feet of women of all ages who are either wealthy or wish to appear wealthy. She also provides soft drinks to men waiting in cars for their wives and mistresses.

Her shift ends around the time yours begins, and since you live on adjacent streets, you frequently pass each other on your ways to and from work. Sometimes you don’t, and then you walk your bicycle by the salon to catch a glimpse of her inside. For her part, she seems fascinated by the video shop, and stares with particular interest at the ever-changing posters and DVD covers. She does not stare at you, but when your eyes meet, she does not look away.

Every so often it happens that you don’t pass her on your way to work and also don’t see her when you walk by the windows of the salon. On these occasions you wonder where she might have gone. Perhaps she has a rotating day off in addition to the day the salon shuts. Such arrangements are, after all, not unheard of.

One winter evening, when it is already dark, and the two of you approach each other in the unlit alley that cuts through the factories, she speaks to you.

‘You know a lot about movies?’ she asks.

You get off your bicycle. ‘I know everything about movies.’

She doesn’t slow down. ‘Can you get me the best one? The one that’s most popular?’

‘Sure.’ You turn to keep pace with her. ‘You have a player to watch it on?’

‘I will. Stop following me.’

You halt as though at the lip of a precipice.

That night a video is quietly stolen from your shop. You carry it under your tunic the following day, but there is no sign of the pretty girl, neither on the way to work nor at her salon. You next see her the day after, her shawl half-heartedly draped over her head in a disdainful nod to the accepted norms of your neighbourhood, as it always is when she is out on the street. She walks awkwardly, burdened with a large plastic bag containing a carton for a combination television and DVD player.

‘Where did you get that?’ you ask.

‘A gift. My movie?’

‘Here.’

‘Drop it in the bag.’

You do. ‘That looks heavy. Can I help?’

‘No. Anyway you’re like me. Skinny.’

‘I’m strong.’

‘I didn’t say we weren’t strong.’

She continues on her way, adding nothing further, not even a thank you. You spend the rest of the evening in turmoil. Yes, you have spoken to the pretty girl twice. But she has given you no sign that she intends to speak to you again. Moreover, the strong-versus-skinny debate has been raging in your head for some time, so her comments cut close to the bone.

When asked why, despite your regular workouts, your physique looks nothing like his in photos of him at his competitive prime, your neighbour, the bodybuilder turned gunman, blames your diet. You are not getting enough protein.

‘You’re also young,’ he says, leaning against his doorway and taking a hit on his joint while a little girl clings to his leg. ‘You won’t be at your max for another few years. But don’t worry about it. You’re tough. Not just here.’ He taps your bicep, which you flex surreptitiously beneath your tunic. ‘But here.’ He taps you between the eyes. ‘That’s why the other kids usually don’t mess with you.’

‘Not because they know I know you?’

He winks. ‘That too.’

It’s true that you have earned a savage reputation in the street brawls that break out among the boys of your neighbourhood. But the issue of protein is one that rankles. These are relatively good times for your family. With one less mouth to feed since your sister returned to the village, and three earners since you joined your father and brother in employment, your household’s per-capita income is at an all-time high.

Still, protein is prohibitively expensive. Chicken is served in your home on the rarest of occasions, and red meat is a luxury to be enjoyed solely at grand celebrations, such as weddings, for which hosts save for many years. Lentils and spinach are of course staples of your diet, but vegetable protein is not the same thing as the animal stuff. After debt payments and donations to needy extended relatives, your immediate family is only able to afford a dozen eggs per week, or four each for your mother, brother and you, and a half-litre of milk per day, of which your share works out to half a glass.

For the past several months, your one secret indulgence, which you are both deeply guilty about and fiercely committed to, has been the daily purchase of a quarter-litre packet of milk. This consumes 10 per cent of your salary, the precise amount of a raise you neglected to inform your father you had received. Per week, your milk habit is also roughly equivalent to the price your employer’s customers are willing to pay for the delivery of one pirated DVD, a fact that alternately angers you in its preposterousness and soothes you by putting your theft from your family into diminished perspective. The daily sum of money involved is, after all, worth a mere thumb’s-width slice of a disc of plastic.

You are thinking of your complicated protein situation when you spy the pretty girl the next evening. This time she stops in the alley, produces the DVD you gave her and thumps it without a word against your chest.

‘You didn’t like it?’

‘I liked it.’

‘You can keep it. It’s a gift.’

Her face hardens. ‘I don’t want gifts from you.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Do you have a phone?’

‘Yes.’

‘Give it to me.’

‘Well, the problem is it’s from work . . .’

She laughs. It is the first time you have seen her do so. It makes her look young. Or rather, since she is in fact young and normally appears more mature than her years, it makes her look her age.

She says, ‘Don’t worry. I’m not going to take it with me.’

You hand over your phone. She presses the keys and a single note emerges from her bag before she hangs up.

She says, ‘Now I have your number.’

‘And I have

yours.’ You try to match her cool tone. It is unclear to you if you succeed, but in any case she is already walking away.

Because of the nature of your work and the need to be able to reach you on your delivery rounds at any moment, your employer has provided you with a mobile. It is a flimsy, third-hand device, but a source of considerable pride nonetheless. Paying for outbound calls is your own responsibility, so you maintain a bare minimum of credit in your account. Tonight, though, you rush to buy a sizeable refill card in anticipation.

But the call you are waiting for does not come. And when you try calling the pretty girl, she does not answer.

Deflated, you go about the rest of your deliveries without enthusiasm. Only at the end of your shift, after midnight, does she ring.

‘Hi,’ she says.

‘Hi.’

‘I want another movie.’

‘Which one?’

‘I don’t know. Tell me about the one I just saw.’

‘You want to see it again?’

She laughs. Twice in one night. You are pleased.

‘No, you idiot. I want to know more about it.’

‘Like what?’

‘Like everything. Who’s in it? What else have they done? What do people talk about when they talk about it? Why is it popular?’

So you tell her. At first you stick to what you know, and when that runs out, and she asks for more, you say what you imagine could be plausible, and when she asks for even more, you venture into outright invention until she tells you she has heard enough.

‘So how much of that was true?’ she asks.

‘Less than half. But definitely some.’

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

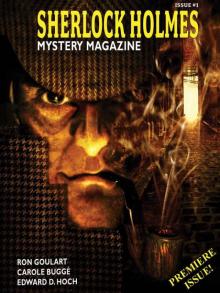

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1