- Home

- Неизвестный

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Page 30

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Read online

Page 30

During the last days of the holiday my father left for Germany to conclude his business affairs and to consult with doctors. And the doctors directed my father to the city of Wiesbaden. Kaila then came to our home to help me with the household chores.

We soon found a young maidservant and Kaila returned to my father’s home. The girl came for only two to three hours a day and not more. I then said, How will I manage all the housework by myself ? But soon enough I realized it was far better to have the servant come for a few hours than for the entire day, for she would leave after completing her duties and then there was no one to keep me from talking to my husband as much as I pleased.

Winter came. Wood and potatoes were stored indoors. My husband labored over his book chronicling the history of the Jews in our town and I cooked fine and savory dishes. After the meal we would go out for a walk, or else we would stay at home and read. And Mrs. Gottlieb gave me an apron she had sewn for me. Akaviah caught sight of me in the large apron and called me mistress of the household. And I was happy being mistress of the house.

But l times change. I began to resent cooking. At night I would spread a thin layer of butter on a slice of bread and hand it to my husband. And if the maidservant did not cook lunch then we did not eat. Even preparing a light meal burdened me. One Sunday the servant did not come and I sat in my husband’s room, for that day we had only one stove going. I was motionless as a stone. I knew my husband could not work if I sat with him in the room, as he was accustomed to working without anyone else present. But I did not rise and leave, nor did I stir from my place. I could not rise. I undressed in his room and bid him to arrange my clothes. And I shuddered in fear lest he approach me, for I was deeply ashamed. And Mrs. Gottlieb said, “The first three months will pass and you will be yourself again.” My husband’s misfortune shocked me and gave me no rest. Was he not born to be a bachelor? Why then had I robbed him of his peace? I longed to die, for I was a snare unto Akaviah. Night and day I prayed to God to deliver me of a girl who would tend to all his needs after my death.

My father is back from Wiesbaden. He has retired from his business, though not wanting to remain idle he spends two or three hours a day with the man who bought his business. And he comes to visit us at night, not counting those nights when it rains, for on such nights the doctor has forbidden him to venture out of the house. He arrives bearing apples or a bottle of wine or a book from his bookshelf—a gift for my husband. Then, being fond of reading the papers, he relates to us the news of the day. Sometimes he asks my husband about his work and grows embarrassed as he speaks to him. Other times my father talks of the great cities he has seen while traveling on business. Akaviah listens like a village boy. Is this the student who came from Vienna and spoke to my mother and her parents about the wonders of the capital? How happy I am that they have something to talk about. Whenever they speak together I recall the exchange between Job and his friends, for they speak in a similar manner. One speaks and the other answers. Such is their way every night. And I stand vigilant, lest my father and my husband quarrel. The child within me grows from day to day. All day I think of nothing but him. I knit my child a shirt and have bought him a cradle. And the midwife comes every so often to see how I am faring. I am almost a mother.

A night chill envelopes the countryside. We sit in our rooms and our rooms are suffused with warmth and light. Akaviah sets his notebooks aside and comes up to me and embraces me. And he sings a lullaby. Suddenly his face clouds over and he falls silent. I do not ask what causes this, but am glad when my father comes home. My father takes out a pair of slippers and a red cap—presents for the child. “Thank you, grandfather,” I say in a child’s piping voice. At supper even my father agrees to eat from the dishes I prepared today. We speak of the child about to be born. Now I glance at my father’s face and now at my husband’s. I behold the two men and long to cry, to cry in my mother’s bosom. Has my husband’s sullen mood brought this about, or does a spirit dwell in womankind? My father and my husband sit at the table, their faces shining upon me. By dint of their love and compassion, each resembles the other. Evil has seventy faces and love has but one face.

I then thought of the son of Gottlieb’s brother on the day Gottlieb came to his brother’s home and his brother’s wife sat with her son. Gottlieb lifted the boy up in the air and danced, but his brother entered and the boy glanced now at Gottlieb and now at his brother, and he turned his face away from them both and in a fit of tears he flung his arms out to his mother.

So end the chronicles of Tirtza.

In my room at night, as my husband bent over his work and I was afraid of disturbing him, I sat alone and wrote my memoirs. Sometimes I would ask myself, Why have I written my memoirs, what new things have I seen and what do I wish to leave behind? Then I would say: It is to find solace in writing, and so I wrote all that is written in this book.

David Fogel

Facing the Sea

Translated by Daniel Silverstone*

* The translator would like to thank Zvia Walden, whose help has made this translation possible. This translation is dedicated to Esther Silverstone.—D.S.

Chapter one

Madam Bremon said:—Make yourselves at home. There’s no one here all day.—Her wrinkled face seemed smaller beneath a wide-brimmed straw hat. She stopped washing the linen by the garden wall. In the room she showed them, an opaque, hot, viscous darkness had jelled, because the shutters had been closed so long. Adolph Barth kept wiping his forehead.—Anyway, you’re facing the sea. Twenty yards. Go! Out with you, Bijou!—She scolded the bleary-eyed black-and-white spotted puppy that was entangled between her feet.

—Yes, we are facing the sea.–Adolph Barth and his companion exchanged whispers.—Good enough. We’ll stay.

Toward evening, when the heat had passed, they brought their suitcases from the train station. The sea was spread out in its richest blue. Fisherman drifted from the shore, spreading their nets from boats scattered here and there across the horizon. In the garden nearby, the tables were set for supper.

Gina lay back languorously on a colorful beach towel. She wore a light green cotton bathing suit that accentuated her shapeliness. A flowered Chinese parasol planted in the ground behind her blossomed above her head. Next to her, Barth, in sunglasses, fingered the searing gravel and flicked pebbles into the water.

Dull brown nets, from which wafted the acrid odor of fish and brine, were spread out to dry behind them. The air just above the ground trembled with the heat.

Cici came out of the water and sat beside them, folding his legs Oriental-style. Droplets clung to his matted chest.—The water is warm,—he said with an accent, obviously Italian.

—You’re shaking.

—I’ve been in the water for over an hour.

Gina rolled onto her side facing the two men, Cici and Barth. Flies hovered over a forgotten little fish left beside a nearby boat that had been drawn out of the water.

—In three days you have managed to tan a bit, madam.—Cici’s eyes wandered over the roundness of her pale thighs. He moved himself closer and compared his skin, the color of copper coins, to hers, as pale as ivory.

—No, not yet like yours.—And to Barth:—Put your hat on, or lie next to me under the umbrella.

—So what is your real name?—asked Barth.

—Francesco Adasso. But everyone here calls me Cici. —And after a moment:—My friend from Rome is here this morning. He is the translator from Cook’s, you know. He should be here any moment now.

—Wonderful,—teased Gina.

He offered her a yellow pack of cigarettes. Gina refused. Cici and Barth smoked, lying on their bellies with the sun warming their backs. The sea sprawled motionlessly at their feet. Only on the horizon did a boat drift, dreamlike. But here, next to them, romped Stephano’s brood, half a dozen dirty children aged two and up, giggling, screaming, and splashing water. And to the side, Latzi and Suzi were playing catch with Marcelle, the dark Lyonean who rad

iated charm and youthful vigor—the three of them looked as though they were cast of bronze.

—The girl from Lyon is very beautiful, said Gina to no one in particular.

—She is,—Cici agreed.—But you, madam, are much more beautiful than she.

—Thank you!

Barth smiled with the corner of his mouth and flicked his cigarette butt in a graceful arc.—Suzi’s lipstick seems much too pale. It doesn’t blend with her tan.

—Shiksa taste.

—Aside from that, she is heavy about the middle.

—Latzi is also from Vienna, interjected Cici.

—You mean Budapest…

The Japanese man, in his bathing suit, emerged from a row of houses opposite the beach, crossed the street that ran parallel to the shore, and approached. He seemed taller than most Orientals; his face more clearly outlined. Following him was his companion, a European wearing a robe with huge saffron blossoms, and a light blue ribbon in her hair. She was shorter than he, and ten years older. She struck Gina as someone who was self-assured. The Japanese man dived into the water, while his companion remained with Latzi and Suzi, who had finished playing.

—Yesterday they drank until four again.—Cici knew everyone’s whereabouts here.

—At Stephano’s?

—No. At the Japanese house. A real bacchanal.

—And you?—Barth sat up. He dried his sweaty chest and thighs upon which the gravel had left a florid tattoo. His face was flushed, and locks of flaxen hair stuck to his forehead.

—I didn’t feel like it,—replied Cici.

The translator from Cook’s was dressed like a dandy in the season’s fashion. His dark hair, glistening with grease, stuck to his scalp like a bandage. His face was smooth and bloated. He extended his left hand when Cici introduced him. His right hand, in a black glove, was false.—Ah! So you live in Paris. I know it like the back of my hand.

That the translator knew everything like the back of his hand was immediately clear. He was especially familiar with foreign languages (the arts, if you please!). In Rome he had a friend, a Japanese poetess, evidence of which he brought with him: a book of Japanese poems with its vertical lines— “a gift from her.” He didn’t know how to read it yet, but this Japanese fellow would teach him. It was all arranged. And the lady? Would she be willing to teach German in exchange for an Italian “lesson”?

The “Arab,” so named for his ability to imitate an Arabic accent, lived and worked with Cici, and clung to the translator like his right-hand man. He would punctuate the translator’s words with nodded agreement, prepared to pounce on anyone daring to doubt them.

—Gina rose to swim.

—Please. Wait while I undress—The translator slid behind the beached boat, the “Arab” behind him. After a few minutes he reappeared, naked. The whiteness of his skin contrasted with the tans of the others, making him look immodest. His false hand was left behind among his clothes; the stump of his arm was wrapped in a towel. He dropped the towel, dived into the water, and began to swim. The “Arab” followed close behind.

—Teach me the backstroke,—Gina said to Barth. And then:—I was swimming behind you, but I didn’t have the strength and returned. You tend to go out too far. Don’t let anything happen!

Cici swam in a circle around Gina. Breathlessly and heavily he pumped his arms and legs, making waves.—Look here! Move your arms and legs like this. One-two! One—now you try.

—Gina let herself go, falling back onto Barth’s outstretched arms, which supported her under the water. Close by, Marcelle stood and watched.—You don’t know how to swim on your back, madam? It’s simple. Here!—She dived in and showed her, laughing through shining mouse like teeth.

—And when shall we race, Mademoiselle Marcelle?—asked Barth.

—Any time you like.

—This afternoon, all right?

—If I don’t go to Nice.

—You like the little one, huh?—Gina said to Barth when Marcelle turned away. And to Cici:—Mr. Cici, you must learn the backstroke by tomorrow, understand?—she teased.

The translator and the “Arab” approached. The translator crouched down, lowering himself chin-deep in the chest-high water. He remained in this position while he was near them. Even so, his maimed arm twinkled beneath the clear water. Gina and Cici were splashing each other now, while Barth, arms outstretched like smokestacks, sailed through the crystalline blue water. When he returned, he reminded Gina about lunch. The sun shone now directly overhead. On the main street, facing the sea, was a single row of houses cracked by waves of glowing molten orange. Passersby trampled their shadows underfoot.

Stephano’s grocery three houses down the street from Madam Bremen’s pension was run by his wife—a thin Neapolitan woman of about forty whose body was ravaged by childbearing and hard work. Madam Stephano was never seen outside her territory. She always wore the same dress, which, once white, was now grayed by dirt. Her blue-black hair, always uncombed, hung in tangled clumps, which fell over her wrinkled face. Her bare legs, in tattered cloth shoes as always, were pale white, laced with blue veins. The southern sun had no effect on Madam Stephano’s skin.

Stephano himself was in charge of selling wine and liquor. A robust and burly despot, Stephano, unlike his wife, did not deprive himself of earthly pleasures. He loved to eat well, drink a lot, and love women. He was a bully and a troublemaker with whom people avoided conflict. Between him and the other Neapolitans (most of the town’s inhabitants were Neapolitan and only a few were French), most of whom were related to him and were also named Stephano, existed an everlasting animosity. He kept away from them, as if he were excommunicated.

Besides the flock of little children, the Stephanos had an older son, Joseph, a naval recruit in the nearby port, and a daughter, Jejette. An attractive peasant of sixteen with flushed gums and red eyelashes whose body was buxom and solid, she was good for any sort of work. She helped her parents in the store, worked in the kitchen and did all the housework, ran the café on the rooftop veranda, got drunk with her customers, danced the fox trot and waltz with them to the sounds of the hoarse gramophone, let loose her fleshy parts to stealthy pinches, and laughed loud and often.

—Nice swimming, huh?—Stephano greeted them.

Gina wore only a skimpy bathrobe. The freshness of the water still clung to her face. Stephano set his eyes upon her feverishly.—Hurry, Madam Stephano! I’m famished! Hey, you bastards! Look out for the wine!—Stephano roared across the street at the children who were crawling under a table set for lunch with a large bottle of wine, beneath a shading plane tree.

Madam Stephano and Jejette weighed the butter, cheese, fruits, and vegetables for Gina. Barth studied the tins of preserves stacked on the shelves.

—A child, madam?—Madam Stephano asked, her teeth shining.

—Not yet,—replied Gina.

—Hey! You haven’t fulfilled your obligation, you!—Madam Stephano reproached Barth.—A healthy woman like this, and pretty, too! You know you’re pretty, madam!

—And my husband?—asked Gina.

—Him too, of course! I like him, ha, ha, ha!

—You hear that?—said Barth to Stephano.

Stephano, who was bent over wine crates in the corner, rose to his formidable height.—I agree, ha, ha, ha! My wife and Barth, and me and you, madam. A fair trade, isn’t it?

Jejette spread her lips in a conspirator’s smile.

—I’ll think about it,-Barth said with forced humor.

Stephano raised a full bottle of pink wine and waved it in the air.—You see this? I advise you to take it! Try it and then come and tell me! I’ve never had rose like this before.

—Nice. We’ll try it.

—And some evening, why don’t you stop by my café,—said Stephano as they were leaving.—It’s the world’s meeting place! Come on over and we’ll have a drink together!

In the garden, Madam Bremen, beneath her wide straw hat, was scrubbing her laundry as usual in

the trough by the well. Didi, her three-year-old grandson, tumbled on the ground with Bijou. Didi’s head was large and round, set with bulging eyes. The torpid afternoon was embroidered by the droning hum of flies, Didi’s muffled squealing, and the wet slapping of Madam Bremon’s laundry. As Barth and Gina passed her, Madam Bremon told them that Cici, “that Italian,” she added in a tone of dismissal (the French here, masters of the land, didn’t like the Italians), had stopped by a few minutes ago to return a book that Gina had left on the beach.

Diligently Gina prepared dinner, Barth helping at her side. After a short while, they sat down in the dining room which was wrapped in semidarkness—Didi and Bijou gaping at them, their eyes eagerly following each movement, one with his thumb in his mouth, the other wagging his tail and blinking his bleary eyes.

—Here!—Gina offered them some bread with butter and cheese. Didi swallowed a sardine also, but Bijou turned it down.

The food and rosé left a pleasant weariness in their limbs. Soon after they finished, they retired to their room upstairs. There they remained, naked, two exquisite young bodies, saturated with sun and sea. An evil thought entered Gina’s mind: how good it would be if gorgeous Marcelle were with them now, and maybe another beautiful woman, here, all together, in the rarefied dusk scented with perfume and cologne, and overflowing with the stunning vapors of lust…

Who could have imagined the heart of man?

—Did you finish your soup, Didi?—Mr. Larouette, Madam Bremon’s son-in-law, would ask his son the same question every evening at exactly seven o’clock when he returned from Nice, where he worked as a bookkeeper for a wholesale oil and wine firm. Mr. Larouette was short and broad-shouldered, his legs bowed in the shape of an urn. A straw cap was perched on the tip of his enormous skull. With a habitual motion, he tilted the cap back to his neck and wiped his face down from his forehead.

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

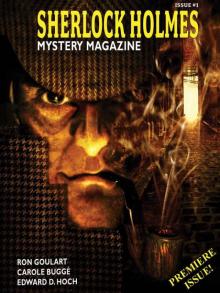

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1