- Home

- Неизвестный

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Page 5

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels Read online

Page 5

On the way Rosa teased him with a strange venom, reminding him with fleet hints of things long repented and best forgotten, such as the time he had clumsily tried to undo the kerchief on her head while they had sat by the window of the drawing room looking out at a stormy night. Mockingly she mimicked his helpless cry of alarm when she had been about to fall in the park, his pointless, repetitive grunts. When he finally left her for the house of a pupil, his legs took him back to the park instead. He climbed the circular railing of the gazebo that stood at one end of the long, straight promenade running from the old castle to a view of the stream at the foot of the park and of a spreading willow tree beyond it. He leaned against the shaky grating, staring down at the round well-house by the stream and at the nearby bin of frozen ashes left over from holiday pig roasts. The white willow was a blur in the thick mist. The cries of the crows assailed and stunned him, told him with a bitter vengeance that people like him could never take what life offered them, had no business living at all. Ka-a ka-a ka-a. He suffered from the childishness, or worse yet, from the simple blind idiocy of the eternal student, which was why he drew a line between his own inner life and his life in the world outside. Ka-a ka-a. Lies, lies. A person was one and the same, forever and aye. Whoever he was in the street outside he was also within his own walls.

After a while he left the park and started back through the marketplace. Breathless men hurried by him and a tall, stocky woman wiped her nose on the back of her hand. At home he took out his notebooks, dimly aware of a throbbing lump in his chest that made him want to cry, and sat down with them at his desk. For a long while he stared at them, nibbling at the cap of his pen while grunting at odd intervals with an effetely nasal sound. And when the spindly, crooked, rat-tailed letters ran from his pen at last, their sickliness so filled him with loathing that he broke off in the middle, threw himself on his bed with a suffering noise, and lay there for hours grunting and tossing in turn.

Yet soon it was nearly spring and the days were filled with light. Patches of soft blue showed through the clash of silvery cymbals in the sky. The sun was new and warm again; golden puddles gleamed underfoot and glimmering streams bubbled gaily. The cows, newly let-out to pasture, rubbed against the walls of the houses, seeking their stored warmth. Hagzar cut back on his lessons. Whenever he could, he went for long walks through the paths and fields, splashing pleasurably through the slick bogs from which a damp glitter arose, breathing in the soft decay of the rutting earth as it warmed, surrendering himself to the steamy mist exhaled by the fat, rank soil.

Now little Ida often dropped by. She was still pale and not yet all over her illness, but there was color in her face and she seemed prettier; her chest had filled out and she was taller too. Wrapped in her shawl she would knock on his door and announce with a fetching smile that she simply could not have stayed indoors a minute longer. It was so, so good to be out in the fresh air now. One might almost…ah! And Hagzar would sit her down by his side and stroke her hair and ask whether Rosa was free yet, and had the three of them lunched, and what was Manya doing, and was her tutor there, and would she please tell Rosa for him that he would soon come himself.

He and Rosa now went walking a great deal outside of town. Light-heartedly they leaped over the ruined snow that still lay piled in the ditches, chatting gaily as they sank into the slick mud of the dark, steaming fields. By the time they tramped home again they were pleasantly numb and their fingers were frozen to the bone; shivering they warmed themselves indoors and swore how good it had been. Sometimes they found Manya standing before the door, half-whistling, half-puffing some Russian tune, the lapels of her black jacket that she had draped over her back held with one hand at the throat.

“Whistling, eh?” Hagzar would jeer dryly.

And Rosa would smile while Manya looked spitefully back at him and puffed through her lips even more.

Yet when she was alone in the house with Ida, Manya spoke often about spiritual suffering that no words could describe; about doubts that preyed on the mind; about gifts gone to waste and dark nights of the soul; about the horrors of drink and the lower depths; about great cities; about freedom, life, and strong wings; and about the need to escape—yes, to escape in the name of all that was holy since she could not go on living like this anymore.

Sometimes her tutor still appeared. Despite the gleam in his restless eyes and his hair that was as charmingly rumpled as ever, his face was drawn and he walked with an unsteady gait. Wearily he harangued them, smelling of brandy and beating his chest with one fist. Not for the first time he declared that only a worm would spend all its days in the dirt; anyone with the breath of life in him, with a bit of pluck and independence, would leave a swamp like this as fast as he could. Where was he bound for then? For a moment a lock of loose hair tumbled gorgeously down. Ha! They needn’t worry about that. Wherever he fell, he would always land on his feet…and meanwhile, was he really such a bad sort to have around?

And he would dramatically raise one hand and declaim with artistic flair:

Myórtvii v gróbe mírno spi

Zhíznyu pólzuisya, zhivói!

Who among them did not know those immortal lines of Nadson’s?

At such times Hagzar would glance at Manya, who sat perfectly still while the faint reflection of her tutor’s smile struggled over her face, and decide that she was not nearly so attractive as he had once thought. On the contrary: her features were on the coarse side and even annoyingly dull. One look at the rapt stare with which she regarded that chest-thumping brute was ample proof of what a dunce she was.

Later, on his evening walk with Rosa, he would murmur to her how detestably mean he found Manya, how put off he was by her vulgarity, how depressed she left him feeling each time. Gradually he shifted to how quickly young people grew up nowadays, how nothing ever stayed the same, and how little there was in human life to hold on to. Even when you considered what still might lie ahead…to say nothing of what you had already seen, heard, and knew…even then life always seemed to slip sideways and to come to nothing in the end. Was that all there was to it?

Did she understand him?

Wasn’t it like this?

And Rosa would cough a gentle cough and murmur shyly and not at all clearly:

“Mm-hmmm.”

Which made him turn even more crimson. His breath came in spurts, one hand pawed the air, and there was unspoken anguish when he said:

“Lately I…it’s not just that I can’t write…it’s…everything. And yet it’s not anything either, eh? It’s just that the more you look at things, the less they are what you think. Something is wrong with them…or perhaps nothing is…and yet there you are…”

Generally he broke off at this point to add after a while in an exasperatedly tormented whisper, shrugging his shoulders in despair: “Unless that’s simply how it’s meant to be…”

At which he spat loudly and exclaimed under his breath: “Phheww…the devil knows!”

And fell silent. An evening gloom cloaked the dull fields and was woven into the cold mist that arose from them. Here and there a solitary willow still stood out. They walked without breaking the silence, treading the soft earth. Now and then he hummed through his nose a quiet, plaintive air that her thin, quavering voice took up. Once she stopped to tell him that her fingers were numb and that she had forgotten to bring her gloves. Yet when he tried putting one of her hands in his pocket, the pocket proved too small, so that his own hand was left outside, holding the sleeve of her coat. Soon they felt how unnatural this was, since it forced them to walk with a limp. After a while she pulled her hand free, and they walked on humming to themselves.

Chapter three

Simha Baer came home before Passover. For several days Hagzar stayed away from the house. The day after her father’s return Ida dropped by. Her face was pale and wistful, as in the old days. She flitted from one thing to another, did not stay long, and giggled when she left that her father was eager to meet him.

/>

Then Manya came by. She kept glancing out the window, inquired about some book whose name she instantly forgot, whistled, promised to come back again soon, and dashed home. When she returned she sat by the window again before remembering that she had left her father by himself and must attend to him. Soon she came back a third time, yet before long she spied her tutor passing by on his way to her house. She ran out to greet him and disappeared for the rest of the day.

But Rosa did not come at all, which left Hagzar feeling as once he had felt when the mailman had delivered a letter to her and she had sat reading it silently to herself in his presence before slipping it into her pocket without comment. An injured, contrary mood settled darkly over him and spewed its bile of loneliness into his blood.

That night he paced endlessly up and down like a man with a toothache, from time to time emitting a sickly, irascible cough that sounded more like a groan. And when he went to bed at last, pulling the blanket over him, the despairing thought assailed him that his surroundings had won in the end, and that the mark they had left on him could never be removed.

The next morning he rose early, thinking of his work. The crooked, rat-tailed letters flashed before him and he stalked the room some more, trying to shake off the scaly sensation of tedium that afflicted him at such times while groggily pondering a dream he had had in which he had finished a long article and was about to set forth on a European tour. At last he picked up an old essay and leafed through it, absently searching for a certain passage that never failed to bring a modest smile to his lips. He thumbed the notebook rapidly, threw it down, picked it up again, put it down once more, and finally opened it a third time and let his glance fall on a page. Slowly his face brightened. His eyes began to glow and his steps grew quicker; feverishly he tugged at his mustache with shaky fingers while making little, resolute grunts in his chest. When his legs wearied at last from their forced march he sat down to work at his desk, humming little snatches of a tune beneath his breath; yet just then the mailman came with a postcard, whose arrival so pleased him that he read it over three times. He rose and paced some more until his head spun, then put on his coat and went out.

In the distance he saw Rosa coming toward him in the company of Hanna Heler. She greeted him like a long-lost friend, and he extended the postcard to her with a sheepish grin before turning in his dry manner to Hanna and advising her to peruse it as well, since it appeared to pertain to her too; they might look at it all, he replied, when both asked at once how much they should read of it. So Rosa read the whole card out loud, already smiling before she began, while Hanna stared at her with a wide-open mouth in whose wings a smile waited too. Then both shrieked with laughter and Hagzar joined in heartily. Now they all knew that Gavriel Carmel, who was once a tutor in this town, had written from abroad to announce that he wished to see his Naples one more time before he died, to which end Hagzar should prepare for him:

1) Attractive quarters; 2) Attractive young ladies; 3) Two or three pupils if possible.

Still the same joker as ever!

Then Hagzar retraced his steps with them and listened to Hanna assure him that she remembered Carmel quite well: a tall, dark young man who had seemed to her rather odd but certainly clever enough. The three of them chatted until Rosa went her way, and Hanna hesitated a moment before accepting Hagzar’s invitation to come back with him to his room. There she kept rising every few minutes to go and sitting down again, the tower of dark hair on her head describing a weak arc around her ample bosom with each loud, staccato laugh. And when Hagzar rose to walk her to the door the thought crossed his mind that she was in fact a dear thing and really very feminine at that. For a second he thought of Manya’s dull stare, of her irritating whistle, and of her jacket draped around her back. Outside the sun was celebrating spring. Rivulets of water splashed gaily by, puddles gleamed like gold, metal shovels scraped against the ice. Roly-poly children frolicked and sang, and Hagzar cried with roguish glee:

“How much light and life there is, Hanna! No, I won’t allow you to go home now.”

Soon they were walking in an orchard high above town. Fresh blades of grass pushed up through the earth and the sodden trees stood resurrected from their sleep. The scattered tin roofs and white churches beneath them shrank and all but vanished in the great expanse of open fields that ran in all directions as far as the dew-bright woods that ringed the broad horizon. The scent of the wakened hills in their lungs roused them too. They grew gay, and he cuffed her lightly on the nose in a giddy burst of affection and called in a whinnying voice:

“Ho, Hanna!”

Which made her laugh loudly and ask if he had taken leave of his senses and would he please—but how strangely in earnest she seemed!—“act his age.” Yet in the end she had to slap his hand and order him to behave. Then his face lost its shape and his eyes darted moistly.

“But a kiss, Hanna…” he lisped, cocking his head to one side. “What’s wrong with one little kiss?”

Again her laugh rang out, propelling the top half of her forward: she could not, for the life of her, control herself any longer, she would simply split her sides, so help her! What kind of strange creature was he? She would give a pretty penny to know who had taught him such tricks. Was it Rosa and her brood? And to think that she had always thought…well, well!

For a moment she looked at him reproachfully; yet his flushed, sheepish face forestalled her with a guilty smile and he seized her full palm with a timorous hand and stammered out:

“But what have I done to you, Hanna?”

Followed more boldly by:

“After all, why not?”

And then in jest:

“A person might think that I had bit you!”

With which he was in fine fettle again. They wandered along the bare paths, laughing each time they collided while vigorously trampling the dead growth beneath their feet. He strode now in triumph beside her, his right arm the master of her shoulder and hair, thinking distractedly at the same time, exactly why he did not know, that with Rosa, let alone Manya, such a thing could never have happened, even though life was the same all over and all the women in the world were simply one great woman in the end.

Hanna Heler returned the squeeze of his hand and looked up at him brightly. Soon they found a fallen log to rest on …

Later that day Hagzar descended with large steps the several stairs leading up to Hanna’s house and stopped at the bottom of them to regard the fair sight of the broad, empty, reposeful street, the low houses alongside it, each neatly in its place, and the tranquil, pure, untroubled sky above. He thrust out his chest and turned with slow, sure strides to go home. Before long he felt as though a thin layer of something were peeling away inside him—peeling, flaking, and breaking up into small bubbles that slid quickly upward to press against his chest and burst into his throat. With surprising ease they tumbled out and he muttered to himself with satisfaction:

“So it’s done then.”

The words sent a rush of blood to his cheeks. He quickened his pace and clapped his hat on his head with one hand. Stubbornly he growled:

“And yet what nonsense, though!”

Despite the speed with which he walked it was already evening by the time the marketplace was behind him. Coal fires gleamed with a ruddy warmth in some of the stores. Farmers urged home their horses, shutters slammed with a metallic bang. He slowed down again, locking his hands behind his back and dragging his stick in the mud. From time to time he squeezed a stubborn cough from his chest, and when he reached home he shut the door behind him and repeated out loud to the still, dark room:

“Yes, what nonsense!”

He glanced at the house across the street, whose drawn curtains were lit from within. He removed a box of matches from his pocket, cast it on the table, made his way in the dark to his bed, and sank into the mountain of pillows upon it; then he rose and walked about the room until his knees were weak and his chest began to ache. An enervating slackness sp

read through his limbs and his brain felt stupidly blank. Again he collapsed on the pillows and lay there a long while without moving, feebly musing how pointless was the life of self-denial and how some people were born to it nonetheless—which seemed to console him, so that he fell asleep thinking of the subtle, soapy odor given off by Hanna Heler’s white breasts.

On his way home one day during the Passover holiday he passed by the pleasant house and saw Simha Baer and Rosa sitting together on the bench that stood in the front yard by their gate. He greeted her without stopping; yet she jumped quickly up from her seat and called to him to come in. Where had he disappeared to lately? She introduced him to her father, made room for him on the bench, and coughed gently all in one breath. Hagzar stammered an embarrassed apology and sat by her side, while Simha Baer proffered a hand, stared down at the ground, and said as though explaining to himself:

“Aha…so this must be your Hagzar…”

Rosa laughed embarrassedly too and confessed:

“Yes, papa, it’s our Hagzar.”

Whereupon Simha Baer grunted contentedly and began to inquire into Hagzar’s past and present life. He listened carefully to the answers with his head studiously bowed, picking mildly at his bearded chin, until something appeared to please him and he broke in:

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

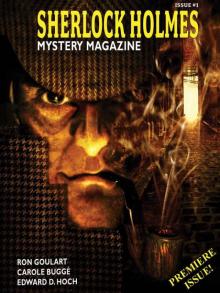

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1