- Home

- Неизвестный

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Page 7

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Read online

Page 7

‘You don’t have to come to my rescue.’ He flung out a hand and it struck her across the breast ... she saw the instant shock register on his face as the feel of her was transmitted from his fingers to his brain.

An exclamation in Dutch broke from his lips and she could feel him looking right at her and yet not seeing her white skin where the mark of his hand was still visible.

‘You must forgive me!’ Yet his face was like iron as he said the words. ‘I had no idea—you have just bathed, of course, and I blundered in like the blind fool I am. I will go—‘

‘No, not like that,’ she caught at his arm, ‘thinking you have done something terrible. You stumbled and couldn’t help yourself, and what does it matter if I have no clothes on? You—you were a surgeon—the human body is no mystery to you, mynheer. You went down with an awful thud. Are you all right?’

‘I—I am fine.’ He rose to his feet and stood there, fumb ling a hand across his hair. ‘I had no right to invade your privacy—I have embarrassed you, and I struck you. Are you sure?’

‘I hardly felt it.’ A statement that was totally untrue, for where his hand had been her skin still tingled, not so much from the pain of the blow but from the intimacy of it, his fingers against the bare soft curving of her body. Her teeth fastened upon her bottom lip. She had to pray that the incident had been too swift for him to have realised that she was smoothly firm where a much older woman would have lost muscle tone. She jerked the damp hair out of her eyes and felt a nerve twitching in her lip.

‘This is no moment for tragedy, Un bel di,’ he mocked, as if sensing her distress. ‘You are not Madam Butterfly and I am certainly not Pinkerton. Direct me to the shutters, but first put on your robe.’

Merlin fumbled with it, a kimono wrap patterned with persimmons, one of several garments she had purchased down in the kampong, from the women who sewed the charming things by hand. Then she reached out and lightly took his hand, and he moved with her to where the big teak shutters were still folded back against the wall.

‘Now I can manage.’ He drew his hand from hers, rather curtly, and it brushed the silky material of her kimono. He frowned as he began to adjust the shutters over the wind-shaken windows. . . what was going through his mind, she wondered, that for a starchy spinster she had a suspiciously exotic taste in bedroom apparel?

Now her room was dark but for the pools of lamplight and she was so consumed by the awareness of Paul in the intimacy of her bedroom that she drew as far away as possible from another accidental encounter with his hand.

She stood there, clad as if for Madam Butterfly, but the scene was straight out of Samson et Dalila and stark in her mind was the way Paul had stumbled and fallen to his knees, all that decisive self-assurance he had once possessed so lost to him that a mere rug could trip him, and she tried to imagine how hellish it must be for a blind man to feel himself falling. She felt a sudden wetness at the edges of her eyes and her throat ached as he turned from the closed shutters and stood there, so outwardly tall and in command of himself.

‘Are there any pictures on the walls that could fall and cause you an injury?’ he asked.

She quickly brushed a hand across her blurred vision and glanced around the Jade Room, so called because of the lovely green colour of the walls and ceiling. There were several paintings, but they were made on silk, the feathery brush strokes of an oriental artist whose trees and figures were dreamlike, leaning over insubstantial bridges.

‘A few small paintings,’ she told Paul. ‘Chinese, I think. Rather lovely in a strange sort of way.’

‘Ah, then leave them where they are. You like your room? You have now grown accustomed to sleeping here?’

‘Yes, it’s a most attractive room, a great deal different from the bedsitter I had before I came here.’ She flinched from a mental picture of that drab boarding-house just off the Tottenham Road

, those worn stairs leading up to the dingy landing, and that eternal smell of boiled cabbage and cheap floor polish. ‘You can have no idea, mynheer, how glamorous my surroundings seem to me after lodgings in a rather dreary part of London.’

‘Will you still regard this place as glamorous, I wonder, if we live through this night, you and I?’

‘I—I hope so. And it does seem like night already, so dark and stormy outside, with the lamps lit inside.’

He gazed around him, eyebrows drawn together, as if he were trying to imagine how the room looked, and what it was like to see the glow of lamps. He knew the furniture was carved teak, and the drapings of eastern silk ... was he picturing against this background a skinny, glamour-starved, drab-haired woman who had spent most of her life in those grey shadows reserved for the lonely and unloved? That was the image she had deliberately created for herself, and he wasn’t to know that as her hair dried against the silk of the silvery kimono it had a honey-ambered gleam in the lamplight, matching her eyes fixed upon his brooding face.

Then he moved, taking a step forward. ‘Are there any more of those rugs lying in wait to trip me?’ he asked.

‘I—I’ll show you to the door, mynheer.’ As she moved across to him the kimono made a soft, silky sound around her bare legs, then she felt his fingers within hers, tense as iron, as she led him to the door.

‘It isn’t like me to be confused like this,’ he said, with sudden harshness. ‘It must be the weather—tell me something, you are wearing a silk wrap, aren’t you? What colour is it?’

‘A silvery shade—sort of grey,’ she added hastily, for grey seemed more appropriate to the image he must carry of her ... she dared not let him imagine that the kimono somehow made her appealing, with its wide sleeves and pearly sheen.

Then, before she realised his intention, he had suddenly moved his hand inside her right sleeve and she felt his ringers enclose the slimness of her bare arm. She couldn’t help it, but his touch thrilled her to the base of her spine, those sensitive fingertips playing against her skin, so unbearably exciting, yet she had to martyr her feelings and snatch her arm out of his reach. But she wasn’t quick enough, and his fingers had locked like a steel shackle around her wrist and she could feel his thumb pressed against her pounding pulse.

‘You’re as nervous as a kitten,’ he said. ‘Is it me, or that typhoon somewhere out there?’

‘Th-the wind is awfully high-pitched, and I’ve never heard rain like that before, like showers of knives falling out of the sky on to the roof.’ There was no controlling the excited race of her pulse and Merlin knew it; all she could hope was that Paul would think her highly-strung state was due to the storm.

‘You don’t like a man to touch you, do you?’ he said. ‘I can feel it, sense it. Have you always been this way?’

Merlin gazed up at him, her eyes filled with his face, her slim body aching all over for the touch she had to deny. ‘I suppose I have, doctor,’ she had to play it lightly or go out of her head. ‘There’s a word for it, isn’t there? Frigidity? Plain women develop the symptom in order to avoid being ridiculed. It wouldn’t do, would it, for a dried-up maiden lady to exhibit any awareness of sexuality. Over the years it becomes second nature and in the end my sort are repelled when a man puts his hand on us—but you were a medical man and I suppose I’m silly to mind if you—take my pulse.’

‘Is that what I’m doing, mevrouw?

‘Yes, you’re counting my heartbeat and you’re wondering if I shall run amok when the typhoon reaches its climax. I shan’t, you know. Old maids are very strong-willed. It comes of standing on their own two feet without the assistance of a man. You really won’t have to tie me down. I shall get our lunch and try not to break all the plates.’

The high tension of the moment was increased by the mounting brutality of the wind that seemed to take hold of the shutters and give them a malevolent shake. Merlin saw the blinding white flash of the lightning through the ribs of the shutters, glaring over the house like the eye of a monster that waited to destroy it. She shivered and felt the bite of Paul’s

finger into her flesh and bone, holding her like a doll in front of him while the mental images jagged in and out of her mind ... the waves filled with violence as they swept in over the beach ... the rattan roofs of the village houses gradually torn into shreds, their sheltering palms a welter of broken fronds.

Eden at the mercy of the angry gods ... it was no use, she couldn’t live on an island like this one and not be affected by the prevailing belief in the old pagan gods, and there was something so overpowering in the wind and the lashing rain and the lightning that flared so fiercely it seemed as if it must burn the sky.

‘Yes, it’s getting worse,’ Paul said, reading her mind even if he couldn’t see the dismay on her face. ‘I warned you, and though you spoke just now with a brave flippancy, all that clamour is going to increase until your nerves start to go to shreds. Face it, Miss Lakeside! You are holed up in a house with a man who can be thrown on his face by a rug. You are utterly and absolutely alone with me, mevrouw, and God alone knows how long this storm will go on. It may not abate until the morning, and in the meantime it will be hell let loose and it may well kill us.

‘Tell me,’ he shook her wrist, hurtfully, ‘did you realise when you applied to come here as my secretary that there are no idyllic places on this earth and that we pay for every bite of the apple that we take? Eden, my dear woman, is a myth and a fantasy. There’s no lasting paradise for anyone!’

‘I’m not a child,’ she rejoined. ‘I didn’t come here with the notion of finding—paradise. I came, knowing what I might have to face up to.’

Words that were of far more significance than he realised, for she had known that she might have to face an emotional storm that would be even harder to bear than a natural one. Her every moment on Pulau-Indah was menaced, and he was the waiting force that could rip her apart.

‘A woman of character, eh?’ But he wasn’t mocking her, and Merlin saw a thoughtful look on his face a moment or two before he released her wrist from his fingers. ‘Come downstairs as soon as you are dressed, and bring with you anything you might require during the day. It will be safer downstairs, to a certain extent.’

He turned to the door and walked away with that firm tread that would deceive anyone who didn’t know that he was blind; she stood there and listened until he reached the stairs, where his footsteps were more deliberate, more careful, as he descended to the ground floor. Then she slowly relaxed and went to the clothes cupboard, where she stood for a moment debating what to wear. She supposed she ought to choose something sensible, just in case the worst happened and they found themselves scrambling about in mud and water, but when she reached inside the cupboard Merlin didn’t choose a pair of slacks and sweater, she chose instead a long thick silk skirt in tulip-red and a shirt of ivory shantung. If she and Paul were in possible danger of annihilation, then she wasn’t going to spend her last hours on earth clad in drab, functional clothes.

With a smile that was just a little reckless she laid the tulip-coloured skirt across her bed, along with the sil shirt. Then she took her best lingerie from the drawer and a pair of sheer tights. Almost with a sense of going to a party Merlin dressed herself, and afterwards she sat at the dressing-table and arranged her hair as she had seen some of the island women arrange theirs, rolled to the crown of her head in the style called split-peach, which she secured with a gemmed pin.

Her eyes looked enormous in the lamplight, gazing back at her from the depths of the mirror, and the tiny mole at the corner of her left eye seemed to blend with the oriental hairstyle to give her a rather exotic look. She ran a powder-puff over her skin and applied colour to her lips. When she stood up the mirror gave back to her a slender, unusual image, and she couldn’t suppress a little sigh. If only Paul might see her and, perhaps, like her a little bit.

Like her? If Paul ever found out who she was, then he’d hate her ... with a hatred as black as the blindness she had helped to cause.

She stared at herself and wondered what the devil she was doing dressing up like this. Paul would hear the whispering movement of her long skirt and wonder if the storm had sent her out of her mind. He’d think her an idiot, and she was ... playing the role of Delilah up to the hilt!

Yet she couldn’t bring herself to change into something sensible ... the pillars of this house might be brought down on her head, and Paul’s, and for once in her life she wanted to be dressed for the occasion. Even if Paul couldn’t see her, he would sense that she was as elegantly dressed as if they were dining at a smart restaurant instead of waiting for a typhoon to come hurtling down on the great thatched roof of the Tiger House.

With a defiant tilt to her chin Merlin applied a little perfume rod to the backs of her ears and the pool of her throat, even the inner bend of her elbows. It wasn’t a discreet dash of lavendel, but a scent which had been purposely mixed for her in a cave-like shop in the village bazaar, where in her free time she often wandered, mixing with the islanders, making friends with them, and learning some of their quaint customs.

It was a subtle aroma, with the faintest dash of musk, and for an instant she panicked. Paul, with his heightened senses, would be aware of the exotic scent the moment they were alone together, and it had to be remembered, for it was her only safeguard, that he believed her to be a middle-aged spinster.

Oh lord ... whatever was he going to think? Perhaps she had better wash off the stuff ... and yet it blended with the look she had created for herself, her tortoiseshell hair swept up into the two coiled halves of a split peach, the soft pale silk of her shirt blending into the lush red silk of her skirt. She was reluctant to discard glamour for her usual unremarkable neatness. She was in love, and this might be her last day on earth, and she wanted to sound silky, and to smell scented, when she served Paul with his food ... like one of those graceful girls of the island in the long opalescent wrap-around that made them seem subservient and at the same time so enticing. A girl couldn’t run in a long skirt, and it was a subtle way of letting the man know that she didn’t wish to run away from him.

Merlin stroked her hands down over her hips, fine-boned under the silk. In the past she had never sought to look glamorous, believing that it couldn’t be achieved and she’d end up looking a fool. But something in the island atmosphere had got into her blood, and what she felt for Paul had certainly got into her eyes, into the contours of her face, and even into her hah- which under the touch of her fingers felt as smooth as her silk clothing.

Through the mirror, through the ribs of the shutters, the lightning jabbed like steel knives. Wasn’t this the way the sacrificial girls had gone to face Baal, hair and face beautified, slender body encased in silk, to be lifted on to the flaming mouth of the terrible god and swallowed whole, like some luscious morsel that like the turtle screamed as it died.

Merlin shook her head at herself. ‘You’re crazy,’ she told herself, and turning away from her disturbing reflection she collected her handbag, a couple of books, and a handkerchief, and after turning out the lamps she walked from her room with that grace of movement that a long skirt imparts to a woman.

And Delilah played the harlot, she thought, and Samson lost his eyes!

As she went downstairs the house seemed to pitch and roll like a ship in a storm, but in reality the sensation was in her head, induced by the winds and her heightened nerves. She stood gripping the balustrade, suspended, it seemed, between hell and the strangest of heavens. It was incredible, but here she was in the heart of a storm, in a house which that havoc might wreck, entirely alone with the only person in the world who truly mattered to her. Her heart pounded beneath the silk of her shirt, and the hem of her skirt caressed her ankles as she went on down the stairs, creating a sensuous whispering that she was aware of with her blood even as the noise of the wind-driven rain lashed at her ears.

She saw that the great lanterns of hammered bronze had been taken down from the stairwell, everything movable had been put out of harm’s way and there in the big stone-flagged kitchen she

had to hunt for plates and a salad bowl, having found cold spare-ribs in the larder that would go down rather well with celery, tomatoes and sliced cucumber, with a big stick of bread, and a pot of strong coffee.

All the time she worked Merlin could feel the vibrations in and around the house, the whining pitch of the wind as it tore at a tree, and the way it hurled itself at the storm doors which Paul had firmly closed, pushing items of furniture against them as added protection.

Merlin knew that nothing would keep them safe from the typhoon if when it struck they were at the centre of it, but in the meantime the heavy doors kept the elements from being driven inside and they gave a sense of security that was welcome, for the rain was falling in such torrents that the kitchen felt to Merlin as if it were undersea. A pair of hurricane lamps provided light, and there at the big wooden table she prepared the strangest meal of her life. At last everything was arranged on a trolley, the salad and spare-ribs, with sliced sweet potatoes she had fried in butter. Rice cakes and pickled plums, the long-spouted coffee pot, and cups with sugar and cream.

She wheeled the trolley to the door, not sorry to be leaving the kitchen that echoed with the sounds of the storm. When she reached the hall she called out for Paul, not knowing in which room he intended them to have lunch. She was glancing into the austere dining-room when she heard him at the far end of the hall.

‘This way, mevrouw,’ he called out to her. ‘Ah, I hear the trolley, and I must admit I’m ravenous.’

‘A rather mixed koffietafel,’ she informed him, as she arrived at his side.

‘I smell coffee, and right now I could eat just about anything. It is strange, eh, how danger intensifies our hungers? This, mevrouw, is the room where we shall share the typhoon, and with luck live through it. Please to enter.’

Merlin wheeled the trolley inside, finding the room fairly small and completely walled in lovely old tiles, faded to the hue of dusty blue velvet. It had a heavy teak door and reclining chairs in bamboo. Here again hurricane lamps had been lit, playing an amber light over a lacquered cabinet and a model of a Chinese junk whose ivory-wood and shining wires seemed to be on the move in the quivering light.

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

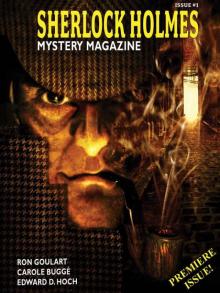

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1