- Home

- Неизвестный

Ghosts in the Machine Page 7

Ghosts in the Machine Read online

Page 7

A ragged boy passed into his view as the sun approached its zenith, clad in scraps of shoddily patched cloth. The child looked terrified to see him, shying away when the unarmed, stripped down warrior beckoned him closer. After some coaxing, the young lad made his way over the remaining pieces of armor scattered about the peak, giving the warrior a moment of pause.

The boy’s movements were...precise. Too precise, as if he was being handled by some unseen force. He found that idea rather absurd, but after such a long period of solitary life the warrior wasn’t about to turn down any human interaction. “You’ve walked up this mountain for some reason, child, but you must explain why. I cannot read your mind.” He tried to put on an air of friendliness, but in his haggard and unarmored state it didn’t seem to impress the boy.

The boy took a hesitant step forward to pick up the discarded, hefty helmet. The steel gave off a dull gleam in the sunlight, but it was enough to put a smile on the boy’s face. He took another step, miniature footprints in the crunchy snow appearing in his wake. A careful gesture set the helmet down in front of the warrior’s feet, just far enough away to be out of his reach. He was no longer concerned about his own equipment, shrugging it off with a vested interest in this boy. “Please, my boy: too much time has passed since I last held counsel with another person. You must have come here to do something more than move my helmet around.”

The next instances of his life flew by too quickly to acknowledge. As the boy opened his mouth to speak the first words he’d heard in some time, a violent shudder overtook the world. The land around him began falling backwards through time, a brilliant white light following the path of a sun setting in reverse. It was bright enough to blind the warrior for a moment and fierce enough to cause him to feel heat within his bones. So sudden was the event that as the light diminished and the sun retreated back beyond the horizon, his stomach lurched with a strength he hadn’t expected.

His eyes opened to see the land submerged in the blackest night once more, a handful of stars doing little to illuminate it. The boy’s small footprints were replaced by fresh, white powder, and the warrior’s helmet was back in its previous resting place as though it had never been moved. Any note of celebration in the valley was absent, and as he looked below the recently disassembled walls were standing tall and bold. The twin voices of doubt and self-deprecation screamed back into life, tittering away at each other in his mind.

With a heavy sigh and an arching of his back, he waited in dejected posture for someone to visit him, prepared to never see another face again. Such was the fate of Danethor the Strong, fearless savior and champion of the mountain, stuck to a bench for all eternity.

A Perfect Apple

Alois Wittwer

It was the second day in her new home when she planted the sapling. It was a small, pitiable thing at first but she would enjoy watching it grow day by day until it finally blossomed into a beautiful apple tree. The fruit was sweet all year round here and she could eat it whenever she wanted. Once grown, the tree would peek out from behind the neighbor's small, wooden house up by the river bank. For a time, it would be a secluded place, and the girl found comfort far away from the hustle and bustle of the village.

Mother had gone to great lengths to warn her of country folk.

"They have no sense of privacy! They come in uninvited and leave your kitchen empty!"

“So? That just means they're comfortable! Have you forgotten what visitors are like?”

“We don't have them in this household for three very good reasons,” she flung her hand up in exasperation. “They'll take all your things and never give them back, they'll ask for ridiculous favours, and they're animals with no sense of morals or public civility.”

“Mother!”

“‘Getting away from it all’ does funny things to your mind, dear.”

***

Her house was small but, despite the dire living situation, the girl felt a deep sense of satisfaction. She'd paid for all of this out of her own pocket (she’d had no choice, really). No, it didn't have amenities or gas, but as the first result of her newfound independence it held immeasurable value. And the house wasn't completely barren. There was a diary and AM/FM radio nestled in two separate corners respectively. The antenna had been snapped off so radio wasn't an option, but she was sure she'd be able to find some old tapes in the village. Much like the tree the girl planted today, her home held unimaginable potential.

Over the next few days, she familiarized herself with her surroundings. Her house was one of four, placed to circle around the others and form a small, paved yard in the center. A notice board stood in the middle of the enclosure but hadn't been used for a long time, frayed around the edges. She knocked on each door. If the girl did have immediate neighbors, no one was home.

She had better luck outside of the square. Most villagers were friendly, some more than others, but she'd done her best not to ruffle anyone's feathers. From what she could gather, no one worked. Poncho, a particularly sociable sort, said he simply sold off the old things he didn't need anymore and lived off the savings. With all the fruit trees around the village, he didn't need to worry about food and could simply live the good life. Everyone could live the good life thanks to the hard work of the local merchant.

The three statues outside the train station remained a mystery to her, however. Placed in front of the crossing, they looked as if they were designed to draw the attention of any visitors or prospective homeowners, carefully sculpted effigies tempting onlookers with dreams of a luxurious new home. One gold, one silver, one bronze, with enough room for a fourth should the need arise, whatever that need was. The statues were carved like monuments but she couldn't recognize who they were supposed to represent.

She visited the lone proprietor of the village and purchased a plain red couch that just barely fit inside her home and a pink vanity the owner described as “simply lovely.” The vanity was for Poncho who seemed obsessed with exercising but didn't have any way to look at himself in his home. Her mother collected furniture like this—old mirrors, brass, reflective surfaces. Abrasive. She didn't want this anywhere near her.

Now she understood why the furniture was so cheap: the customer was expected to carry all goods to their home themselves, no concerns about health and safety, and some items looked unmistakably second-hand. By the time she'd visited Poncho and arrived home, daylight was already fading. Curled up on the couch, the wrinkles of the fabric printed like age onto her skin. Abrasive wasn't a good word to describe her mother.

***

It was Poncho who first suggested she take up morning aerobics to iron out the creases built up from daily training. She wasn't quite sure what he meant but relished the opportunity to start the day early with communal exercise, huddled around the town's local water fountain with friends. A different kind of ritual from what she was used to.

But familiarity persisted. The villagers had, alongside their boastfulness, a tendency to loan things and quickly forget who had them originally. Who had said that to her? At times, the girl felt like little more than a slave forced to do her master’s bidding, ferrying knickknacks back and forth between folks, but most of the time she cared for the villagers as if they were her own children. They were a forgetful bunch, having lived so long in a village that promoted a lack of productivity, so it felt natural that they would gravitate towards the outsider for direction. She didn't want to deal with that pressure tonight. She moved here to get away from this incessant need.

Her Saturday nights were typically spent down by the seashore, fishing for the biggest catch. This was the activity to make a fortune and the heavy rain tonight could coax even the rarest fish out of hiding. A few hours spent fishing each night and you'd never have to worry about money again. Now, she could buy whatever she wanted and renovate her tiny home. It was a welcomed change after living so long in a cramped apartment with her mother. She could never make this sort of money living in the city.

She wouldn't visit the beach tonight, though. Instead she walked through the orchard of orange trees she had planted earlier that week. One of her closest friends in the village, Mitzi, had given her a leftover orange she had lying about as thanks for finding her handkerchief. The girl had never seen an orange in the village before and promptly scattered the seeds across an acre with the hope that they would grow. At first she was worried the saplings didn't have enough water; it had been so hot during the week and she had no way to care for them. But the trees had sprung to life in a lovely criss-cross pattern. It was a bit difficult finding a pathway so late at night, though, even with the soft glow of the moonlight off the oranges, so the girl took a cursory glance over her handiwork and headed back home. Much like everything else she did in the village, the orchard was for herself more than the villagers and besides, they would get lost mos—no, she didn't want to think about them tonight.

As she was walking home, she heard a soft, lilting tune off in the distance, distinct from the gentle pitter-patter of rain on the ground. A funny-looking man sat perched on a little box strumming a guitar under the roof of the train station. He was soaked to the bone, a sad slouch. He played on regardless, to an audience of no one, with a grin that betrayed his tenacity.

He looked up as she approached, resting the guitar on his lap, and told her stories that felt like they came from a book. He was a solitary musician who travelled from town to town playing music to fresh faces each and every night. His music was free and for the people, no fat cats allowed. He seemed to find it fulfilling.

It was midnight when he stopped playing; she stayed the whole night. When she got back home, she found a recording was resting in her pocket. The cassette player snapped open with an urgency common to analog devices, and the girl gently placed the tape inside the cradle and eased it shut. It didn't sound the same—recordings never do—and the speaker was broken.

She was dazzled at how anyone could live like that. Wouldn't it get lonely playing to passing strangers each night with no place to call home? Maybe this was how people were supposed to be like? Her mother didn't have anyone else in her life. Why did she say such horrible things to her? She sat down on the squeaky floorboards until the tape clicked off. She hit rewind and played the song again.

***

The letter arrived in December:

Dear Valentine,

I was thinking about you as I had my morning coffee. Do you remember when you were little, and I gave you a sip? You didn't sleep for days! That was a bad idea.

Live and learn.

Mom.

Her hands froze to the sides of the paper, holding on in the biting cold as she read the message over and over again. This had to be a joke. Who would do this?

Valentine stumbled over to the train station and sat down on the nearest bench, waiting for the next train to come by. She'd get on the next one and leave this place, forever. She didn't care how long she had to wait. She wasn't welcome here. Why did she ever think otherwise?

Hunched over the bench, she held on like death. Valentine waited the whole day; the train never came. The town bell tolled as the hours slowly passed. A small jade monument, just like all of the other statues, had joined the others now in front of the station. The snow fell like ash, hiding its features, blurring her vision, but it was there all the same. The statue was a permanent celebration for everyone who had transformed their small home into a mansion. Valentine had been the last, and it was smaller than the others. She rubbed her eyes with her fingers and, no, it couldn't be her. But it looked like all the others. The same dress and pointy hat, the same exuberant expression, smaller now, unimportant. The statues were all the same. It was just a coincidence this one had been made, right?

The crossing remained still. Nothing more than a decoration. Perhaps a train would come by someday, Valentine thought, and it would be her hearse.

***

The cicadas were singing when Valentine came back. Poncho had left and the goodbye letter he sent to her was a trivial afterthought. She wasn't even sure who actually wrote them anymore. Valentine would have liked to say goodbye to him, though. Despite her distrust of the villagers, Poncho had been good to her. She didn't begrudge him for wanting to find something exciting in his life again. No, she was hurt that her friendship had meant nothing to him.

A grumpy man called Murphy moved into Poncho's lot. He seemed genuinely unhappy to be here. She enjoyed his blithe comments and condescending attitude so much that she made herself uncomfortable.

Valentine couldn't go back to the routine she'd established before. Nothing felt genuine anymore. Once-concerted efforts to donate all the fossils she found buried underground to the local museum slackened. Where were these things even coming from? Maybe the person who knew could also tell her how her house was renovated while she was asleep.

In her wandering to while away the hours of the afternoon, she stumbled upon the old apple tree she'd planted so long ago. It still stood as proudly as before, bearing the same perfect fruit exactly like the moment it first bloomed. Except now the fruit held no finer meaning to her. It was a bland, chewy thing that turned her stomach. As she picked up the leftover fruit off the ground, she realized that this tree would be brimming with apples again within a few days. It would always be producing something. It would never stop.

And the seasons would come and go like always. The years would go by. The salmon would swim upstream for March and the fireflies would illuminate the night sky each June. Halloween, Christmas, and New Years would come and go with crushing mundanity. The villagers would go about the same celebrations. They would leave whenever they felt like it for whatever reason they desired on a train that never materialized, like ghosts.

Except for Valentine.

Valentine had exhausted herself by caring for a village that gave her nothing back. And what had she really done for herself?

She rummaged through her belongings at home; the collection of junk she'd amassed ever since she moved in, searching in vain for something to comfort her. Her house had turned into a museum, filled with collectibles she received for special holidays she'd attended throughout the years. Valentine had nothing that suggested a person lived here. She'd long since gotten rid of her bed to fit in an oversized boxing ring. She didn't need to sleep. When had she last slept?

When had she moved in?

Valentine struggled to remember. No one else would remember. She didn't know anyone else.

She rushed out into the village, desperate to find somebody she could reminisce with. But Poncho and Mitzi had long since moved out of the village. The older villagers that were here when Valentine first moved in had never spent as much time with her, so wrapped up in their own comings and goings. She was a stranger now and, far from finding it invigorating, she was violently alone.

The girl wandered down to the beach and peered out into the inky blackness. She stood in a stillness that could last forever. Were you so sure of yourself, mother? When was the last time she told her she loved her? Valentine had never done something so simple. Why did it matter so much? She just loved a memory now, an empty face.

Murphy walked over to Valentine to wish her a happy birthday. He wanted to be the first. He couldn't sleep.

“How old are you today?”

Valentine paused. Murphy laughed and shrugged off her uncertainty as embarrassment. He knew he wasn't supposed to ask that question. Valentine wasn't embarrassed, though. She honestly couldn't remember how long she'd been here or even where she came from. The uncomfortable silence divided the pair and Murphy made a hasty retreat, gruffly muttering about some furniture he had to buy in the morning. The waves crashed against Valentine's feet and soaked her shoes.

What was she afraid of now? She didn't need to be polite anymore. She didn't have anything to lose.

Valentine returned to the town square, her familiar home surrounded by three strange ones. She knocked on the doors of her neighbors but this time she didn't wait for an answer

. She went inside each house that had ignored her and found immaculate, two-storey homes furnished with stunning furniture and things she'd never seen in the village before. But nothing was out of the ordinary except for the complete lack of any living person. Cockroaches scurried across floors so clean Valentine could eat breakfast off of them. The three houses she'd considered empty had been inhabited—should have been inhabited—but Valentine had never seen anyone else like her in the village before.

Deep in the basement of the last house, Valentine spotted a vanity stuffed awkwardly into a corner, forgotten just like the rest of the homes, spotless, a familiar face reflected back at the girl. The same face frozen in the bust of the statues outside the train station, a happiness with no focus, a happiness stuck in place for eternity.

***

Valentine had forgotten about the shimmering cherry blossoms that littered the sky each April. She never had to plan for this unexplained event each year that painted the entire town in a luminous pink, when the trees dropped petals that looked like watercolor paintings melting in the harsh summer heat. The four statues framed in perfect unison in front of the train station flowers that had refused to wilt despite all the time that passed.

The village was never like this, originally. Valentine had done this but she couldn't remember doing it. Now all sorts of fruits lined the acres in meticulously organized orchards. Flowers, maps, and signposts had been erected to guide any would-be visitors to all of the town's highlights. Poncho and Mitzi had seen this village grow from nothing to a magnificent utopia, and they'd learnt all they could from living here before moving on with their lives. The new villagers, so unfamiliar yet so friendly, shared the same enthusiastic cheer and forgetfulness of Valentine's older companions. Time had changed this forgotten, useless, uncaring village into something wonderful.

The Bolivian Diary

The Bolivian Diary Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive )

Caffeine Blues_ Wake Up to the Hidden Dangers of America's #1 Drug ( PDFDrive ) The Empty House

The Empty House T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)

T Thorn Coyle Evolutionary Witchcraft (pdf)![K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Read online](http://freenovelread.comhttps://picture.efrem.net/img/nienyi/k_j_emrick_and_kathryn_de_winter_-_moonlight_bay_psychic_of_by_chocolate_cake_a-maze-ing_death_retail_epub_preview.jpg) K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub)

K J Emrick & Kathryn De Winter - [Moonlight Bay Psychic Mystery 01-06] - A Friend in; on the Rocks; Feature Presentation; Manor of; by Chocolate Cake; A-Maze-Ing Death (retail) (epub) Next Day of the Condor

Next Day of the Condor Onyx

Onyx The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel

The Woodcock Game: An Italian Mystery Novel Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing)

Granta 122: Betrayal (Granta: The Magazine of New Writing) One More Dream

One More Dream Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed

Cosa Nostra by Emma Nichols) 16656409 (z-lib.org) (1)-compressed Cowboy by J. M. Snyder

Cowboy by J. M. Snyder Colossus

Colossus Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky

Star Trek - DS9 011 - Devil In The Sky Fright Mare-Women Write Horror

Fright Mare-Women Write Horror The Future Is Japanese

The Future Is Japanese In the Witching Hour

In the Witching Hour Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets

Mammoth Books presents Wang's Carpets The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain

The Cradle King: The Life of James VI and I, the First Monarch of a United Great Britain Stalking Moon

Stalking Moon Hostage To The Devil

Hostage To The Devil![Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/23/harris_daisy_-_mere_passion_ocean_shifters_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Passion [Ocean Shifters 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Day, Sunny - Hot in Space (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel

Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology

I Never Thought I'd See You Again: A Novelists Inc. Anthology Billion dollar baby bargain.txt

Billion dollar baby bargain.txt![Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/26/chenery_marisa_-_turquoise_eye_of_horus_egyptian_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Chenery, Marisa - Turquoise Eye of Horus [Egyptian Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Cat Magic

Cat Magic Star Trek - DS9 - Warped

Star Trek - DS9 - Warped Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove

Catherine Coulter - FBI 1 The Cove Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom

Miranda Lee -The Blackmailed Bridegroom The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry Dragon Moon

Dragon Moon The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers

The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers That Is Not Dead

That Is Not Dead Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror)

Best New Horror: Volume 25 (Mammoth Book of Best New Horror) This Christmas by J. M. Snyder

This Christmas by J. M. Snyder Faerie Cake Dead

Faerie Cake Dead CS-Dante's Twins

CS-Dante's Twins EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing)

EFD1: Starship Goodwords (EFD Anthology Series from Carrick Publishing) Echo Burning by Lee Child

Echo Burning by Lee Child The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2010 Wild Hearts

Wild Hearts Violet Winspear - Sinner ...

Violet Winspear - Sinner ... Broken Angels

Broken Angels FearNoEvil

FearNoEvil![Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/santiago_lara_-_range_war_bride_tasty_treats_11_siren_publishing_polyamour_preview.jpg) Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour)

Santiago, Lara - Range War Bride [Tasty Treats 11] (Siren Publishing PolyAmour) 8 Great Hebrew Short Novels

8 Great Hebrew Short Novels This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death

This Is How You Die: Stories of the Inscrutable, Infallible, Inescapable Machine of Death The Steampowered Globe

The Steampowered Globe While We Wait by J. M. Snyder

While We Wait by J. M. Snyder Iron Tongue cr-4

Iron Tongue cr-4![Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/stieg_larsson_millennium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_v5_0_lit_preview.jpg) Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT)

Stieg Larsson [Millennium 02] The Girl Who Played with Fire v5.0 (LIT) The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009

The Spinetinglers Anthology 2009 Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic)

Bowles, Jan - Branded by the Texas Rancher (Siren Publishing Classic) Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More)

Brown, Berengaria - Vivienne's Vacation (Siren Publishing Ménage and More) Inheritors

Inheritors Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters

Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance)

Cunningham, Pat - Coyote Moon (BookStrand Publishing Romance) Static Line

Static Line Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology)

Ghost Mysteries & Sassy Witches (Cozy Mystery Multi-Novel Anthology) Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love

Elizabeth Neff Walker - Puppy Love Ghosts in the Machine

Ghosts in the Machine Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6)

Theater of the Crime (Alan Stewart and Vera Deward Murder Mysteries Book 6) Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series)

Red Satin Lips, Book One (The Surrender Series) Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge

Catherine Coulter - FBI 4 The Edge StateoftheUnion

StateoftheUnion Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House

Fantastic Women: 18 Tales of the Surreal and the Sublime from Tin House Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original

Sara Wood-Expectant Mistress original Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job

Nine-to-Five Fantasies: Tales of Sex on the Job Granta 133

Granta 133 Dream Quest

Dream Quest The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2

The Warlock in Spite of Himself wisoh-2 Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour)

Glenn, Stormy - Mating Heat (Siren Publishing Ménage Amour) Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic)

Davis, Lexie - Toys from Santa (Siren Publishing Classic) Once Dead, Twice Shy

Once Dead, Twice Shy McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories

McSweeney's Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages

Zombies: Shambling Through the Ages Baghdad Without a Map

Baghdad Without a Map Banshee Cries (the walker papers)

Banshee Cries (the walker papers) Fire and Fog cr-5

Fire and Fog cr-5 The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas

The Twelve Hot Days of Christmas The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance

The Relations of Vapor: Dot - Connivance![Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/harris_daisy_-_mere_temptation_ocean_shifters_1_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Harris, Daisy - Mere Temptation [Ocean Shifters 1] (Siren Publishing Classic) World of Mazes cr-3

World of Mazes cr-3 Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26)

Mistaken Identity (A Jules Poiret Mystery Book 26) Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor

Star Trek - DS9 - Fall of Terok Nor Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver)

Not Like I'm Jealous or Anything: The Jealousy Book (Ruby Oliver) Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder

Skaterboy by J. M. Snyder The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2

The Sorcerer_s Skull cr-2 The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series)

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature (Modern Asian Literature Series) New Erotica 5

New Erotica 5 Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target

Catherine Coulter - FBI 3 The Target Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture

Best Sex Writing 2013: The State of Today's Sexual Culture Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity Huia Short Stories 11

Huia Short Stories 11 Call of the Wilds

Call of the Wilds Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)

Great English Short Stories (Dover Thrift Editions)![Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/ramagos_tonya_-_logans_lessons_sunset_cowboys_2_siren_publishing_classic_preview.jpg) Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)

Ramagos, Tonya - Logan's Lessons [Sunset Cowboys 2] (Siren Publishing Classic)![Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/morgan_nicole_-_sweet_redemption_sweet_awakenings_1_siren_publishing_allure_preview.jpg) Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure)

Morgan, Nicole - Sweet Redemption [Sweet Awakenings 1] (Siren Publishing Allure) Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight!

Warbirds of Mars: Stories of the Fight! Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit)

Original Version of Edited Godwin Stories(lit) Where The Hell is Boulevard?

Where The Hell is Boulevard?![Chemical [se]X Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/chemical_sex_preview.jpg) Chemical [se]X

Chemical [se]X Allison Brennan - See No Evil

Allison Brennan - See No Evil Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1

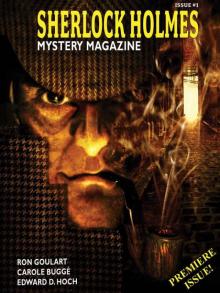

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #1